Number 9 January 2007

Ordeal by Readership

I survived! At the 2006 Reunion, Raymond Rowe said very kind things about my first effort with the newsletter, and a number of you have expressed similar sentiments subsequently. Thank you, I must have done something right. I do have a little worry at the moment however. Where no photos are supplied with contributions I like to insert photos or graphics which have some relevance to subject matter of an article to relieve the acres of text and give the publication a less dense feel. You will see what I mean in this issue. However, you might feel that this is an unacceptable use of space which could otherwise have been used to include another contribution or two. Are there too many pictures and too few words? Please let me know what you think, by post, email, or in person at the reunion in April.

Not many contributions came in over the last twelve months, so I have dipped into the backlog going back to ’05. Some of the articles are extracts from much longer pieces. Anyone who has a memories of the company – amusing and lightweight, serious and thoughtful, from the trivial to the technical (but not too technical) – please jot them down and send them in, with pictures if you have them. They don’t need to be lengthy: the longer the article the more the cutting and editing I have to do! And on the subject of the backlog, you will recall that a number of articles were to have been posted on the website: this didn’t happen but I promise that this year it will. The first to appear, barring any technical hitches, will be the MIMCO Manager D Robertson’s report to London following his release from Japanese internment in 1945. Any posted on the website will appear in their entirety.

New Street site – the latest

Peter Turrall, Vice Chairman, Marconi Veterans Association

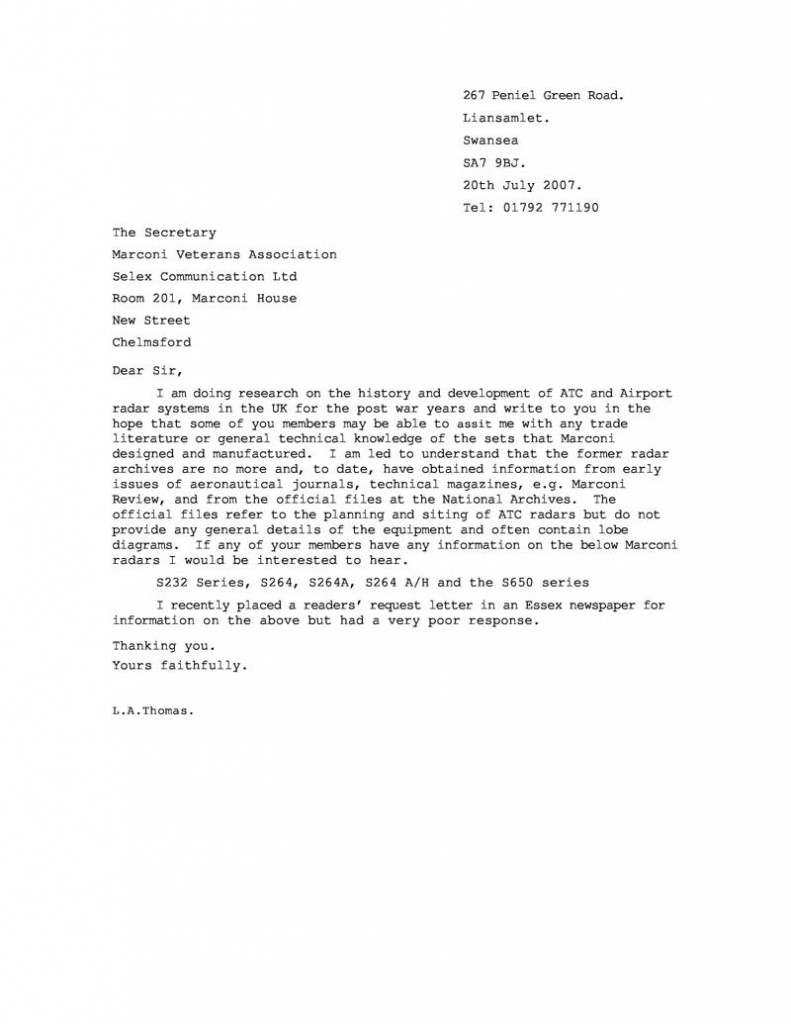

Messrs Ashwell Developments of Cambridge, the owners of the Marconi Communication Systems site at New Street, now occupied by Selex Communications, are in regular consultation with the Planning Department of Chelmsford Borough Council concerning the proposed development of this valuable nine and a half acre site.

An outline planning proposal has been submitted which covers the removal of several of the large buildings and the complete removal of the factory. The 1912 front building which already has a preservation order on it, will remain, although there will be several modifications to cover possibly an area for exhibition of Marconi products and a few offices. Despite previous rumours this building will not become a hotel.

The large four storey Marconi House and Building 720 with the corrugated roof will also be removed, allowing the site to have shops and residential areas laid out with gardens and a heritage walkway which will depict the history of our company.

Part of the area adjacent to the New Street Security Office and close to the railway line will be removed, allowing a walkway and road which will lead to the railway station. The Power House and the two cottages plus the tower on the opposite side of the railway line will remain. It is hoped in this area some of the company’s artefacts can be on view with possibly modern presentation facilities of voices of past employees and also film footage.

To ensure the history of the company and its employees is preserved, the undersigned has joined with the developers and their heritage and conservation experts in some of the planning and decision making areas. Over the coming months a team of photographers and audio crew will be contacting many ex-employees to obtain stories of life within the company during their employment. If you are interested in this aspect, then please contact the Editor who will be pleased to pass on this information. If you have any artefacts which could be permanently loaned, then these could form part of the heritage trail through the site. Your assistance in this latter respect would be most welcome.

|

On page 12 of the last issue, Stanley Fisher promised to send a recent photograph of him standing outside the main New Street entrance. It seems appropriate to place it here accompanying Peter Turrall’s news of the proposals for the New Street site. |

Mailbag

The Baddow Photo

In the last newsletter, on page 5, we carried a picture of a group of Baddow engineers taken in 1939. The location of the photo was uncertain, and there were gaps in the list of names. I’ve received two letters on the subject, from Ian Butt and Cyril Marshall.

Ian Butt writes:

It shows (on the front row) Percy Beanland and FE Sainsbury as numbers 14 and 15 – I think this should be 12 and 13. Â I hope with returns from the Veterans you may be able to publish a more complete list of who’s who, since most of the engineers/boffins were really at the forefront of Marconi’s later expertise in new design etc, apart from all the technology that appeared during World War II.

I assume you know that Chick (Mac) Mackenzie died recently.

From Cyril Marshall:

Roy Simons comments on the photo did trigger my memory of those times. I was in the Test Department at New Street in 1934, having joined the company in 1929 as an apprentice. I agree with Roy in that the photo was taken at Writtle, not Baddow. However, I’m certain that Mervyn Morgan is number 10 in the back row. I recognise a few more faces:- second row 5 JF Hatch, 7 VJ Cooper, 8 NW Jenkins, and 15 in the back row is Watts from R&D Workshops. Front row 13 FWJ Sainsbury, I remember him as a tall person and responsible for the Sainsbury design equipment cabinet. Like Roy, there are other faces that I recognise but am unable to remember names.

On Colwyn Bay Wireless College

Richard Shaw

Peter Robinson’s news of Colwyn Bay Wireless College was of particular interest, since I was a student there in 1941-42 before joining the Marconi Marine Company, and I have been able to pass news of its website to another old boy who was there in 1948. We first met in 1982 when I came to live in a village near here and he and his family were next door but one. We both worked for the Marconi Company in its various incarnations until our retirements, and he was delighted to have the news. I had returned to the Wireless College in 1948, just missing my future colleague who left the previous term, and enjoyed another eight years or so at sea and three on the shore staff in Cardiff.

Regarding Marconi’s statue, I find its treatment by the Borough Council (which commissioned it) quite disgraceful. Of course it should stand in the centre of Chelmsford. If it were not for Marconi, Chelmsford would have been neither wealthy nor famous, but just another county town. Its councillors need a damn good talking to!

I was sorry to read of the death of John Sutherland who, as Managing Director of Marconi Radar Systems, presented me with my certificate as a Marconi Veteran. I recall that we could have either a presentation watch or a sum of money worth rather less.

As I already had a watch but was rather short of the other, and my car battery was nearing its end, I asked for a replacement (obtainable at a discount from a local garage) instead of the watch, and the balance in cash! I think he was a little surprised by my unusual request, but granted it nevertheless, thereby making me probably the only Marconi Veteran whose membership presentation included a chit for a lead acid battery.

Pleased the association still exists

Bernard de Neumann

I’m very pleased to see that the Marconi Veterans’ Association still exists, as I thought it had become defunct since I no longer receive any mailings from you. (Prof de Neumann is one of the lost and found referred to at the end of this newsletter. Ed.)

I became a Marconi Veteran in 1986/7 I think: I joined Marconi Research Labs as a mathematician in ‘Mathematical Analysis’ of Mathematical Physics with Jozef Skwirzynski. I left MRL in 1988 to take up an appointment as Professor of Mathematics at The City University, London, and am now retired.

You may care to note for the newsletter that a portrait of me by the noted artist John Wonnacott, won the 2005 Ondaatje Prize (£10,000 plus a gold medal) of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters last May. See for example: http://news.bbc.co.Uk/2/hi/entertainment/4486329.stm Consequentially, as a professional mathematician, I have now added to my cv that I am mathematical model – and am, somewhat uniquely, a living breathing example rather than an idealised representation!

The wisdom of the Saturday supplements

To steal ideas from one person is plagiarism – to steal from many is research.

Experience is something you don’t get until just after you need it.

Report of the 2006 Veterans’ reunion

The 70th annual reunion was held, as usual, at the MASC in Beehive Lane Chelmsford. Our president this year, Veteran Raymond Rowe, was introduced by Veteran Ewan Fenn. Raymond’s working life as an engineer from 1946 to 1988 spanned a wide spectrum of technologies from microwave link through space communications and troposcatter to broadcasting. He joined Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company as an engineer in the HDB Group at Writtle in 1955, and save for a very brief interlude at Cossors in the 60s, he remained with the company until his retirement in 1988 whilst acting Divisional Manager of Broadcasting Division.

In his reply, Raymond detailed some of the highlights of his career, and of the Marconi Company. Some quotes from his speech that are worthy of note.

‘If there was a place in the world in trouble then either we (in Marconi) had been there just before or we soon would be.’

‘Who knows what else there is to come. I believe we probably saw the best of it; the work was still very much hands on. The engineers of today, because of the computer interface, are a bit more remote from the end product…’

‘So we were there at a very influential period of Marconi’s, probably the most important time since the beginning of radio. The name Marconi did not need explaining to any one that I met in my travels for the company.’

‘As Marconi Veterans we perhaps do not really understand how important our group is. We are among the relatively few who really knew what Marconi’s meant. I am sure that all of us are proud that we can trace our company back to the beginnings of radio.’

Raymond then introduced the Guest of Honour, Robert Wellbeloved C.Eng, FIEE. Bob was formerly Chief Engineer (Transmitter Operations) for the IBA and latterly an independent consultant for many UK and overseas organisations, mainly on Digital TV transmissions. He joined Marconi Communication Systems in 1956 on a four year Graduate Apprenticeship followed by installation work on behalf of Broadcasting Division before joining the ITA in 1965 as a Transmitter Engineer.

In his speech Bob noted that is was just 50 years since he had joined Marconi-MWT. He used 50 years as his theme and posed three questions – what would he have done differently over the last 50 years, what have been the most significant changes over this time, and would he have preferred a different 50 year period for his working life?

The answer to the first was – very little. In responding to the second question he cast a wry eye over many things that have changed in the last 50 years, some good, some bad, but even some of the goods were not unalloyed.

He would not have wished to change the time slot of his career and noted that the late Victorian era had abysmal living standards and a much lower life expectancy. The early 20th century had two world wars and the depression. And would he like to be leaving University in 2006 with the prospect of working until 2060? Definitely not!

Veterans’ reunion 2007

The 2007 reunion will take place on Saturday 14th April at the MASC, Beehive Lane, Chelmsford, commencing at 1.00pm. This year’s President is Professor Roy W Simons, OBE, CEng. Roy served with the company for 43 years, joining MWT in 1943 with the major part of his career in radar. In 1965, with the restructuring of the Company, he became Technical Manager of Radar Division, and with the subsequent merger with GEC, he was appointed Technical Director of Marconi Radar Systems, a post that he held until just before his very busy retirement in 1986. His leisure time is devoted to a number of musical interests. He will be introduced by Marconi Veterans’ Association Chairman Charles Rand, previously Works Manager at Writtle Road.

The Guest of Honour will be Dr John C Williams OBE, FREng, Hon FIEE who for a number of years was Director of The Marconi Research Centre at Gt Baddow, Chelmsford and later was Secretary and Chief Executive of the Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE) in London.

News from Kwazulu Natal

Barry Powell received the following email from Jack Mayhew last March:

Many thanks for the latest news letter which I have just received. It is very much appreciated. I must give you my latest postal address as we have just moved. (Barry has the address for anyone wishing to contact Jack). We have a magnificent view from our new house and can see the Indian Ocean in the far distance. Unfortunately a few weeks before we moved I had a stroke but I am pleased to say that although I was paralysed down one side I am now able to walk a few steps again. Please pass my congratulations to Ken, the new editor of the newsletter, but please ask him if and when he uses my name again would he please add the last three letters to my surname! Kindest regards.

Jack refers to the item on page 10 of the last issue, under ‘Some more Marconi bibliography’, attributed to Jack May. I was thrown by his email username – jackmay. Many apologies Jack. Ed.

What’s the rate of exchange for kudos?

Eric Walker

This extract from a much longer piece by Eric Walker – for all of his Marconi career an Airadio man – focuses on some of the less serious aspects of the life of the avionics (although I’m not sure that the term was in common parlance then) engineers inhabiting the Writtle huts in the 50s. Mike Lawrence, who served in the DO at Writtle and for a while at Basildon, has expanded Eric’s original article with additional material and turned it into a hand-crafted booklet with a very limited production run – Eric and Mike both have two copies, the Writtle village archivist another and there is a sixth copy at the Sandford Mill Musuem. It is well worth reading in its entirety, and we shall endeavour to make it accessible on the website.

When I arrived at Writtle in 1951 we were housed in wooden huts. The only brick-built facility was the workshop. Historically, Les Mullin’s team occupied the original 2MT (2 Emma Tock) hut of early broadcast fame, in which part of the 1922 installation was still visible. Geoffrey Beck’s Air Navigational Aids team occupied a relatively new wooden Hut A. We later expanded to Hut AK as our team grew in number and parallel projects were undertaken.

Beck’s team was formed to develop Green Satin, a military project funded on a cost-plus basis by the Ministry of Supply. The equipment is well-described in Chapter 42 of W J Baker’s ‘History of the Marconi Company’. Briefly, it was a self-contained airborne navigational aid, which used the Doppler effect to measure the ground speed and drift angle of an aircraft from which present position and other navigational attributes could be deduced.  ‘Self-contained’ means independent of ground-based aids. The accuracy of Green Satin depended on high-precision waveguides in its aerial, both in dimensions and in the slotting process which was coped with by Charlie Swanborough in the waveguide section at New Street.

| Green Satin was a considerable step forward in the art of air navigation. The project derived from work done at TRE Malvern, a Ministry establishment, by Johnny Clegg and George Thorne. Experimental models had been made by Mervyn Morgan’s team at Baddow and we, at Writtle, had to develop a design into production, just as fast as we could. The programme was classified secret and was urgent, as it was needed for the Canberra aircraft and the V bomber force (Valiant, Victor and Vulcan, although only the latter two were fitted). We handmade eight development models followed by thirty ‘crash-production’ models before full production was undertaken at the New Street works.

Green Satin was a challenging project to a very tight timescale. It was an exciting programme for a team of mainly young engineers to work on, and we worked very hard, with good team spirit.

Starting time was 7.45am in the workshops and 8.15am for design staff; and we clocked-in. Knocking-off time was supposed to be 5pm, but we rarely left until much later. We worked 6 days a week and often on Sundays when the programme required us to. The notion was, if something needed doing you stayed and did it. The only times you left work unfinished was when it was not possible to complete it for one reason or another. This habit of working long hours stayed with many of us even when the pressure finally came off. You felt you were letting the team down if you worked to the clock. Those who did leave on time, for domestic reasons, usually took briefcases of papers home with them. |

|

Jumping ahead a bit, when we had successfully put Green Satin into production, Bernard MacLarty came to thank us and said that our efforts had earned kudos for the company. We were brash enough to ask what the rate of exchange for kudos was and if it would benefit us? He took it in good part. But there seemed not to be such a thing as a bonus in those days. The idea was that if you did a good job you might move up the ladder and take on more responsibility for perhaps more pay. I saw records of staff reviews where senior management debated at length whether Bloggs should receive an increment of £12 or £15 per annum.

Our work, though intense, had plenty of fun in it. On Guy Fawkes day rockets were fired, suspended on a wire strung from near the hut to down the field. Fireworks figured quite a lot at other times. Much skill was put into secreting bundles of bangers in other peoples’ workplaces, which went off when you (or they) operated power switches. The ballistics expert was Ray Walls. But Arthur Adam earned the medal for concealment. One evening we blew up a bundle we had dropped between the walls of his hut (AK). Next morning, when we came to work, we searched our hut for the response we knew must be there. In vain. He waited until mid-morning before activating it. He must have worked half the night to put in the subterranean wiring. Beck put a stop to it after that, for fear of fire, or mayhem.

|

Our hut was very cold in the winter, the only heat coming from a few hot-water radiators (by courtesy of the stoker Bill Crabb) and of course the heat generated by the concentration of bodies and active high-powered equipment and test gear. In the summer it was too hot, even with open windows. We had a water tap and basin in the hut, so the bright-ideas squad, led again by Ray Walls, ran a suitably punctured hosepipe along the ridge of the hut roof. Water pressure was then adjusted until drips just came off the eaves before evaporating. Much experiment was needed to get the leak wetting pattern just right to cover the roof.

Such activities as these greatly amused EB Greenwood, manager of the newly-erected Basildon Works, who visited us often. He particularly liked our system of warning that our door had been opened, combined with the means of shutting it again. A Heath Robinson device comprising pulleys, angle-iron, a large loose nut and a bell (acoustic). What tickled Greenwood was that it was ridiculous, in such a small hut with so many inhabitants. |

No project really ends, even when it is in service. Much remains to be done in the way of support, training and maintenance. A significant time is reached when most work is done by ancillary staff and the key designers move onto new programmes. When this happened, in 1954, we decided to commemorate Green Satin and its design team by placing a brass plaque on the roof-supporting beams of Hut A. I had it engraved in the workshop. It said ‘On this site was designed the world’s first airborne Doppler navigational aid to become a standard service equipment’. Not very inspiring: not even grammatical. But the project was still secret (and remained under wraps for another 3 years) so very little could be said. Besides, it was a small plaque. With the low cunning of a Marconi apprentice, Ray Walls screwed it onto the beam, having filed the screw heads so they could be driven in, but not out. The plaque was there long after we left in 1960. We had intended to reclaim it if and when the hut was no longer in use. But the site, in Lawford Lane, is now a housing estate. I wonder what happened to the plaque? Sad really.

A landmark on the Writtle site was the Lancaster aeroplane. It was used to try out aerial arrangements and various other installations. People wondered how it arrived there – did it fly in? No, it came by road in bits and was reassembled on site. It was dismantled and disposed of in 1956.

Walter Cook

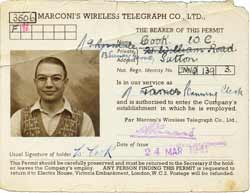

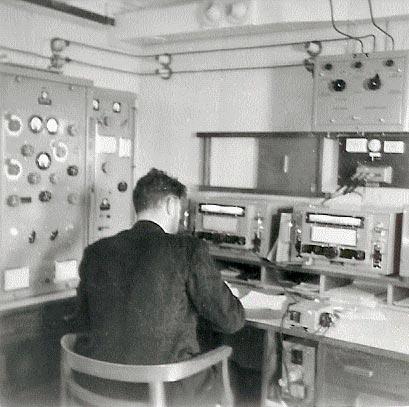

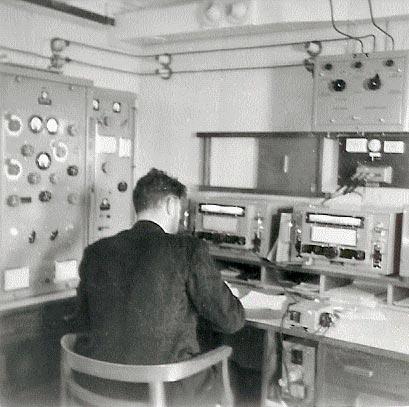

Before work on the previous issue had been started, Martin Cook, a former seagoing Radio Officer based at the East Ham depot and now living in New Zealand, contacted Barry Powell about the death of his father Walter Cook on the 20th July 2005. Walter served with the company from 1939 until 1971, at Hackbridge from ’39 to ’47, Writtle from ’47 to ’52, Chelmsford from ’52 to ’64 and Hackbridge again from ’64 to ’71. When Martin was clearing up his effects, he came across these three items which he thought might be of interest to the Veterans’ Association. Walter appears in the top photo, which seems to be taken at a later period than the lower – he doesn’t appear in that one. The identity card was for his time at Hackbridge. Martin has provided the bones of Walter’s cv, but can anyone throw any light on who any of the individuals are, and where the photos were taken.

A plea for information

Hello, I wonder if you could help me.

My name is Don Simpson, I am an employee (1974 – present) of Marconi Radar/MRCSL/Alenia/Marconi/AMS/Bae Systems Insyte (who next?), but I’m interested in my father’s career. I have a little bit of info, but not much, and I can’t get a clear picture from my mother (Dad is now deceased – December 1983)).

His name was Stanley Simpson, he joined Marconi some time round about 1952/3/4 (confusion about the actual date). At that time he was manager (?) of the Electrical Goods department at Perth Co-op (Scotland) and previous to that had been running his own small business servicing accumulator driven radios. His addresses would have been 111, Mildmay Road, Chelmsford, and, after that, Glenorchy, South Street, Great Waltham. His birthdate was 13 August 1909. My understanding is that he was approached by Marconi, either because of articles that he had written into Wireless World, or possibly through his RAF service (he was a radio technician, spent the entire war in Palestine/Kenya).

Would the Association be able to access any employment records that could confirm his employment dates (he left around 1957 to go back to Scotland), his position (I understand he worked at Writtle) or possibly confirm how and why he was approached? I’m just interested to try to find the real facts about him.

Curious that I should have ended up in the same ‘old’ company as him, in the same town again.

Don Simpson, PDM Team Lead, Chelmsford, BAE Systems Insyte.

Barry has explained that the Association has no access to any employment records, and furthermore that they may have been archived so that even HR Departments have difficulty in accessing them. Don’s only hope therefore appears to be one of you. Does anyone remember a Scot, Stanley Simpson, who appears to have worked at Writtle in the mid 50s. Please send any reply to Barry for forwarding to Don.

The Marconi Scientist mystery

| Peter Wyss, an ex-Electro-Optical Advanced Systems Division (Basildon) Veteran, was involved in the Stingray Torpedo project since its inception in the early 70s. Some months ago he was sent by Ted Haydon, also ex-EOASD Veteran, the cutting from the Letters page of the Costa Brava News shown on the right. Peter entered into an exchange of correspondence with Pamela Handford, the writer of the letter, and then emailed a number of former colleagues with the results of this exchange, including your editor because he thought it might be of interest to other Veterans who had worked on Stingray, or with a taste for intrigue, conspiracy theories etc.

Pamela Handford has a number of apparently well-placed contacts all resulting from her group’s involvement with UFO research. The group’s activities have brought them to the attention of US Air Force and Spanish Military Intelligence. Their investigations revealed links to the deaths in suspicious circumstances of 25 Marconi engineers working on the Stingray Torpedo project in the mid/late 80s. An article appeared in Computer News at the time, and a book on the subject was published in 1990, Open Verdict: an account of 25 mysterious deaths in the defence industry, Tony Collins (1990), Sphere Books. Any Veteran with a taste for intrigue, conspiracy theories, ‘spooks’ etc wanting to learn more about this story can contact Peter Wyss through me or Barry Powell. |

Fort Perch Rock Museum

Arising from a conversation with Jimmy Leadbitter, Stan McNally sent Barry Powell the web address for a museum on Merseyside with which he is associated. Fort Perch Rock (near New Brighton) on the Mersey is a former fort from the Napoleonic era. The museum houses many interesting exhibits, an important theme running through them being Merseyside’s maritime past. A recent addition, formally opened last October, is the Merchant Navy Wireless Room which contains Marconi equipment and so may be of interest to Marconi Marine Veterans.

The web address is: http://sco493.co.uk/album34.html

March 1944 – Eindhoven, Chelmsford and RAF Bradwell Bay

Chelmsford area veterans may well have been aware of the publicity given last year to the presence at Sandford Mill Museum of the WW II Luftwaffe relief model of the Marconi and Hoffmans complex in Chelmsford. This brought to mind for MVA chairman Charles Rand the copy in his possession of an article that appeared in the county magazine in 1970 (The unknown airfield – RAF Bradwell Bay, Essex Countryside, December 1970). It concerned the history of RAF Bradwell Bay, a wartime base for light bomber and nightfighter operations – Bradwell nuclear power station stands on part of the site of the airfield. Of interest to Marconi Veterans are the paragraphs concerning the Luftwaffe raid on the Marconi works on the night of the 21st March, 1944, involving one of the nightfighter units based at Bradwell, 488 Squadron equipped with Mosquito Mk XII/XIII. (the Mk XII is pictured below – IWM photo).During winter 1943-4 No. 488 Squadron gradually built up a ‘score’ of enemy aircraft, but there is no doubt that the highlight was the night of March 21, 1944, when the Luftwaffe, as a reprisal for the RAF’s attack on Philips’s Eindhoven factories (which the patriotic Dutch had welcomed), decided to wipe out Marconi, Chelmsford, using a picked force of Junkers 88/188 bombers. Not until long afterwards was it released that Chris Vlotman (the only Dutchman flying night fighters) in shooting down two Ju 88s just off the coast had brought down the leader of the formation and that 488 had destroyed all five of the first ‘pathfinder’ force, two to Squadron Leader Nigel Bunting and the fifth to Flight Lieutenant John Hall. A prisoner, literally blown out of his Junkers, was captured by the Southminster police and the writer helped to hold him as 488’s doctor stitched a gash in his face where the jagged fuselage had caught him as the bomber disintegrated in mid-air.

Later, as the allies entered Germany in 1945, an RAF Regiment officer found on a Luftwaffe base a magnificent model of the Marconi works which had apparently been made for briefing pilots for the attack. This is now in the entrance hall at the Chelmsford offices and Chris Vlotman, now captain of a KLM DC8 jet, flew from Alaska some years ago to be the company’s guest and speaker at a charity dinner-dance for the Trueloves school for physically handicapped boys at Ingatestone.

|

Captain Chris Vlotman, DFC, Netherlands War Cross (left), inspecting the model of the Marconi factories made by the Luftwaffe. With him are Mrs Vlotman, Mr Leslie Hunt, local aviation historian, Mr Neil Sutherland, managing director of Marconi, and ‘Dusty’ Miller, editor of Marconi Magazine. Essex Weekly News photograph. |

|

As indicated in the first paragraph, the model is now of course located at the Sandford Mill Museum in Chelmsford – not all of our heritage disappeared off to Oxford! There is an interesting footnote to this story. Charles Rand didn’t know the source of the article, or the name of the author. In the Essex Chronicle at the beginning of January appeared the report of a local aviation historian, Stephen P Nunn, signing copies in Maldon of his newly published book ‘Maldon, the Dengie and the battle in the skies 1939-1945’. Your editor made contact with him to find out if could throw any light on the source of the article – he could – and it transpired that he is the son of Peter Nunn who was a production engineer with Marconi Communications at Waterhouse Lane until his retirement in the early 90s. Regrettably Peter died in 1995, not long after his retirement, but Charles knew him very well as did no doubt many other Veterans. |

The Baddow Tower – update

In response to Roy Simons’ item and my editorial comments about the history of the CH tower at Baddow, Veteran Bill Fitzgerald sent me a copy of an interview with him which appeared in the Miscellany column of the Essex Chronicle in June 2005. It reported that he was launching a solo campaign to persuade English Heritage to put a preservation order on it, on the grounds that it is the last structurally secure WWII CH radar tower in the country. English Heritage at that time took the view that it was not at risk, because it was still in use. In the accompanying letter Bill reiterated that it is the last remaining CH tower in the UK, but the tower would obviously be at risk should the site be closed down and sold off.

My enquiries to establish the current situation prior to typing this item triggered a flurry of telephone calls, which included The Essex Chronicle telephoning me, but at the time of going to press there is nothing to add. Watch this space.

Radio Officers’ memoirs

Bill Godden

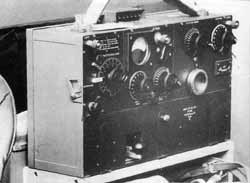

The photo below is the installation fitted by Glasgow Depot, at the beginning of 1957 on board the Lyles Shipping Company’s MV Cape Horn. I joined the ship at Greenock for her maiden voyage in June 1957. The equipment consisted of Oceanspan VI main transmitter, Reliance reserve transmitter, Mercury and Electra main receivers, Vigilant AutoAlarm, Autokey and Alert fixed 500kc/s receiver. All powered by batteries. One of the receiver power packs can be seen under the Morse key, I don’t remember the type number. The ship’s broadcast receiver I think was a Dynatron.

| Of particular interest was that the ship was fitted with one of the few Ultrasonic Antifouling Devices, (a Barnacle Buster), I think there were only ever three fitted. The idea was to set up ultrasonic vibrations through the ship’s hull to stop marine growth, barnacles and the like attaching to the ship.

We had a good maiden voyage lightship down to Cuba, where we loaded bulk sugar in Boqueron and Cienfuegos and took it to Tokyo.

On passage across the Pacific I experienced my first hurricane, Hurricane Kanoa. We were in it for about a week during which time I was sending weather reports to San Francisco Radio, KFS I think, every four hours. From Japan we were lightship down to McKay in Queensland where we took on another load of bulk sugar for Liverpool and Glasgow.

It was October when we arrived back in the UK after a good trip with a good crew. Most of us signed on for the next trip which was supposed to be a six week run down to South Africa and back. The Third Mate organized to get married on return to the UK, but it turned out to be a long six weeks which took us to South Africa, Mozambique, Texas, Japan, Canada, Ocean Island, Nauru, Australia and New Zealand, in all fourteen months. After spending most of the time in the tropics we signed off in Hull in January 1959. The Third Mate did get married to the same girl.

We had some good fun and, at that time it, was common for ships to disappear over the horizon for two or three years. Some blokes were lucky to get happy ships, a lot were unlucky and the trip was misery from beginning to end. I was lucky in this case. |

Felix Mascarenhas

My career in the Marine Company was varied and commenced on the sea staff during the second world war. The Marconi Radio Officer held a unique position on board ship. Although not employed by the shipping company, he came under the direct jurisdiction of the Master and was an integral part of the crew, enjoying the same privileges as the other officers.

I studied to become a Radio Officer at the Wireless College in Colwyn Bay and having passed my ‘ticket’ I joined the Marconi International Marine Communication Company in July 1941. During the war Radio Officers were in short supply. A senior and two juniors were needed to maintain a 24-hour watch on all deep sea merchant ships. The examination for the necessary qualification, which was issued by the Postmaster General, was held at the college under the jurisdiction of a Post Office Marine Wireless Superintendent, whose main duties involved surveying the wireless equipment on merchant vessels. The exam consisted of sending and receiving Morse code in plain language, in code and in figures at various speeds, a written paper on electronic theory, fault finding on the equipment, and a knowledge of Q codes and operating procedures. To indicate the shortage of Radio Officers at that time, a Marconi Personnel Officer from Liverpool depot attended the college after the exam and immediately signed up those who passed. I had a medical examination on the same day and was appointed to my first ship and was at sea within a few days.

Not much is known of the part the Merchant Navy played in the hostilities. One in every five of the 180,000 men who sailed under the Red Ensign were lost, and this figure includes over 1,400 Radio Officers who gave their lives in the fight for freedom. On a percentage basis the losses were higher than any of the armed services with the exception of aircrews. A total of over 2,400 vessels were sunk, or destroyed by enemy action.

For added protection, whenever possible vessels sailed in convoys of possibly twelve vessels across and ten or more deep, covering an area of several square miles. The Commodore ship was positioned in the centre of the front row of vessels. The Commodore, who usually was a retired Vice-Admiral or Captain, controlled the convoy via encoded flag messages which were acknowledged by all the vessels hoisting the same flags. Over twenty Commodores lost their lives in the North Atlantic. Because radio signals could be picked up by submarines and surface raiders strict radio silence was always observed. Convoy protection was provided by several naval vessels made up of destroyers, corvettes and armed merchant trawlers.

Radio traffic was transmitted to ships every four hours from naval coast stations situated in the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries. To ensure that radio silence was maintained the messages were not acknowledged. Instructions from the ships’ owners and/or the Ministry of War Transport were transmitted in code groups of five numbers. Each vessel had a code book containing pages of groups of five numbers. The first two groups in the message indicated where to commence the operation of subtracting the received groups from the numbers in the book. The resulting groups, after subtraction, were then applied to another code book which translated them into plain language. This work was undertaken by the Radio Officer, whose other duties involved keeping a continuous watch on the international distress frequency, listening on the direction-finder for enemy submarines and assisting on the bridge by hoisting flags and signalling with the Aldis lamp. The only time radio silence was broken was when a vessel was attacked. The SOS distress signal was not used, instead SSS was sent to indicate an attack by submarine, AAA an attack by aircraft and RRR an attack by a surface warship.

Deep sea merchant vessels were reasonably well armed. A 4.7 inch gun was mounted on the stern poop-deck. A naval gun-layer and two or three naval ratings manned this weapon, assisted by crew members. A 12-pound anti-aircraft gun on the stern after-deck was manned by two army gunners. Two Oerlikon quick tracer firing guns were mounted on each side of the bridge and two machine guns were mounted on the boat-deck. These were manned by the ship’s crew.

One of my worst wartime experiences happened during my second trip in December 1941. I had been appointed to a very old Cardiff tramp ship. We joined our convoy at Milford Haven but were unable to keep up through lack of speed, probably due to engine trouble, and were left behind. We were ordered to rendezvous with another convoy but again we were not able to keep up due to our poor speed, so we were instructed to proceed to Halifax, Nova Scotia in Canada on our own. The weather worsened, and the storm which lasted for several days was one of the worst that I have ever experienced. We lost our lifeboats, which were slung out over the side for easy access, and our rafts, which were fitted as an extra wartime safety measure, were smashed. The vessel’s superstructure was considerably damaged by the heavy seas. The cabin, which I shared with the Deck Apprentice Officer and the gun-layer, was also damaged due to the deck-head having been torn open when a machine gun was ripped off its mooring by the seas. The cabin heating consisted of a cast-iron coal-burning stove called a ‘bogie’. The excessive draft from the storm force winds caused it to over heat and glow red-hot, and as the deck was awash with water swirling backwards and forwards and over the stove the cabin was filled with clouds of steam. Everything was wet including our bunks. We slept fully clothed with our sea-boots on. It took the best part of four weeks to cross the Atlantic.

I experienced my first encounter with a fatality on board that ship. One of the naval ratings, on leaving his post, was hit by the sea coming over the ship and was not found until daylight the next morning, entangled in the rigging. His burial, attended by all the crew was a sad and unforgettable experience. The ship heaved too, and his body, wrapped in canvas, was put over the side after a short service conducted by the Master.

Halifax was very cold that December and January. The sea water in the harbour was frozen over. To add to our discomfort, repairs to our cabin deck-head were carried out while we were still on board. A large canvas awning was our only protection from the elements. One night the apprentice and I came back from ashore only to find the gun-layer in his bunk completely buried in snow which had emptied into the cabin when the canvas awning had given away. He had previously had quite a few drinks and was oblivious to his perilous predicament. To this day I have never been able to understand the reasoning why this dilapidated old vessel was made a Commodore ship. The Commodore with his complement of naval signallers joined our already over-manned vessel and we lead an 8 knot convoy back to the United Kingdom, fortunately in calm seas via the Arctic Circle without a gun being fired.

At the end of hostilities, conditions gradually returned to normal: only one Radio Officer was required on most ships. As additional equipment became available, such as VHF and UHF-RT sets, single sideband HF-RT, telex, radar, television, closed circuit monitoring equipment, etc, etc, the Radio Officer’s duties increased and became a lot more technical.

I sailed on eighteen different ships ranging from cargo ships, troopships, passenger ships, tankers, bulk-carriers, and tramp ships, during the thirteen years I spent at sea. Each voyage was a different experience. Two of my voyages lasted over two years and two lasted over one year without returning to the United Kingdom. It was an enjoyable and a worthwhile career for a young single man. With some regret I hung up my sea boots in 1953 when I joined the Company’s shore staff at Cardiff depot as a temporary Marine Technical Assistant.

Looking back over more than sixty years to those days of my youth when joining a ship for another voyage was always an adventure, I only choose to remember the good times, the parties on board ship, the nights ashore in far flung ports all over the world, the ships on the Indian coast where the officers even had their own butler, and Gordon’s gin was three rupees a bottle. I often reflect on the hours spent on the bridge at night with the Second Mate somewhere in the vast Pacific ocean picking out the constellations in the star filled sky and marvelling at the magnificence of the Universe.

With the demise of the British Merchant Navy, and the introduction of satellite marine communication systems, the Marconi Radio Officer, like the lamp trimmer, is now surplus to requirements. At the end of hostilities the Marine Company, in its prime, employed 5,500 Radio Officers and had depots and bases and agents situated in ports all over the world. Sadly, very little is left of the once largest marine wireless communication company in the world, but we still have our memories.

Felix now lives in retirement in Dover and invites former colleagues who might be in the area to look him up.

Derek Griess

The appreciation of Derek Griess was published on the website in September 2006, shortly after his death. Â It is repeated in the paper copy of the newsletter.

Baddow Model Shop memories

Rob Wakefield

After reading the latest newsletter I thought I would send you a few lines about the few chaps I work with at Baddow.

I work in the Model Shop with 5 other skilled machinists. I and two others are all Marconi trained and are still very proud to be part of the Marconi history. The news letter transports us back like a time machine as if it were yesterday. The eldest of us came from Pottery Lane, my other colleague from the Radar company and myself from New Street, Bld 29 R&D. Our total service adds up to 104 years. We are all survivors of the collapse of the Marconi company and have ended up together at Baddow. When you think we are the only millers and turners left working on an old Marconi site in Chelmsford – there were hundreds of us with machine shops at Radar, Waterhouse Lane and the largest at New Street – it kind of makes you proud!

You know you’ve had too much of modern living when…

…..you pull up in your drive and use a cellphone to see if anyone is home.

…..you don’t stay in touch with family because they don’t have e-mail.

Military Scout & Wireless Cars

The following is an extract from an article by Harry Edwards which appeared in the Autumn 2004 edition of the Journal of the Morris Register (Harry was a mechanical designer involved in studio design, OB and radar displays and was with Marconi Marine at retirement. He is the editor of the Journal and the Register’s historian). A Marconi connection with the manufacture of the kit may strike a chord with senior Veterans.

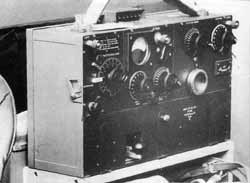

| A number of wooden huts comprised the Signals Experimental Establishment, under Colonel C J Aston, the Officer Commanding at Woolwich Common in 1926, when the development work began on the No.1 Set transmitter/receiver. This was the first design by the SEE to employ both radiotelephony and wireless telegraphy and also the first to be designed to work on the move. It was battery operated and two years later in 1928, it was severely tested by the Oxford University expedition to Greenland.

Although wireless had proved to be of great value to artillery during World War 1, the production of a postwar artillery set was shelved for several years.  An experimental radiotelephone set working on the 10 metre band was given a trial. The use of this band was a bold innovation at the time, but unfortunately a little premature, the set had a communication range of three miles, which was not enough and in any case was insufficiently robust and liable to frequent faults. The artillery was without wireless until the issue of the No.1 set in 1933.

By 1929 considerable experience had been gained in the design of radiotelephone sets and a new series of army wireless sets was formulated. Originally six types were proposed, the No.1 set being for infantry and artillery brigades; the No.2 for divisions; the No.3 for corps; the No.4 for armies; the No.5 for the L of C; and the No.6 for worldwide strategic communications. Subsequently this series was extended to provide for armoured fighting vehicle sets and later for infantry, anti-aircraft and special purposes. |

|

|

Significant features of the new series were, firstly, the inclusion of radiotelephone facilities in the Nos 1, 2 and 3 sets each covering a relatively narrow frequency band. With an overlap between the Nos.1 and 2, and between the Nos. 2 and 3 respectively the total range of the three sets extended from 6.66 to 1.36 MHz (presumably converted from wavelength – I assume this means 1.36 to 6.66MHz. Ed.). It was not considered in 1929 that the use of reflected waves would be feasible for forward tactical communications owing to the vagaries of the skip distance. All these sets were therefore designed to work by ground waves and their communication ranges were limited accordingly.

With the research work and design completed by the Signals Experimental Establishment, it was left to the electronics industry to produce these sets. Manufacturers known to have built and supplied the No.1 sets include Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, H W Sullivan Ltd, and Aeronautical & General Instruments Ltd.

Around the same time the military began to order small cars for use as scout cars. The first of these appear to have been issued to the 11th Hussars and then other Cavalry regiments, and were the unmilitary-like two seater Austin Seven Gordon England Cup models made at Wembley. An initial order of 65 vehicles was later increased. Early in January 1929 an Austin Seven two-seater with a boxlike boot was made for evaluation by the Army by Page and Hunt. Far more military-like was the Austin Seven two-seater design of 1929 by Mulliners. (Assumed to be Mulliners of Birmingham, a name associated with the Austin Seven.). This two-seater was based on the same lines as the Page & Hunt body with a squared off locker at the rear, within clips were provided for the ubiquitous .303 rifle. In addition to the Austin Seven the overhead camshaft Morris Minor chassis was given the same Mulliner style body in February 1929. So far these vehicles appear to have been used as scout cars. In 1932 a War Department approved design for a two-seater wireless car enters the picture, making use of the No.1 Set.

|

This same design was used for both Morris Minor and Austin Seven chassis The boxlike area behind the seats accommodated the radio equipment while a fixed support bracket, bolted to the body side, provided the mounting for the aerial insulator. Published figures suggest that some 176 Austin Sevens of this type went into service, and the writer estimates a total of 169 Morris Minors, most, if not all, based on the 1933 model Morris Minor (see photo left). The writer is not aware of any surviving examples of the Morris versions but a completely restored version of the military Austin Seven, owned by Andy Hodge, complete with the No 1 Set, can usually be seen at the Royal Corps of Signals Museum, Blandford. |

|

Obituaries

Obituaries have been posted on the web site at various times over the past year. A full list for the year is published in the paper copy. All deaths can be found under the “In Memoriam” category on this The latest deaths notified are shown in the index bar on the left. To view earlier notifications please go to the Archive.

Nicholas Swarbrick

From Veteran George Cockburn

This contribution was received from George Cockburn, who felt that, although Nicholas Swarbrick was not a Marconi Veteran, he would have been known to some you and so of interest.

I would like to record the death of Nicholas Swarbrick who died on February 2nd aged 107.

Nicholas was a Merchant Navy Radio officer on the Atlantic Convoys during the 1st World War picking up horses in Nova Scotia for shipment to France and later on the Liverpool/New York run ferrying American troops.

He was born in 1898 at Grimsargh near Preston and gained his Certificate of Proficiency in Liverpool. He never married and I would think he would have been the veteran of veterans.

His obituary was in the Daily Telegraph of 8/2/2006 (I have a copy should it be of interest).

Kind regards

Veteran George Cockburn

(I also have a copy of the obituary. Ed.)

Arthur Adam, 1926 – 2006

Arthur Adam, one of the characters featuring in Eric Walker’s reminiscences on page 4, died on the 2nd March 2006. He was the son of a Professor of Chemistry at Southampton University and a mathematician who worked with Neville Shute Norway on the R100 airship. He joined the company in 1946 after reading engineering at Cambridge.

Francis Faulkner, Eric Walker, Denys Harrison and Ray Walls at the Airadio reunion following Arthur Adam’s funeral service last March. Photo – Brian Ady |

He worked throughout the 50s in Geoffrey Beck’s Airborne Navigational Aids Development team at Writtle, and, outside work, pursued his interest in sailing, photography and bird watching. Denys Harrison relates a number of interesting experiences when their perfectly lawful pursuit of these activities brought them to the attention of the law, the maritime authorities and HM Customs and Excise. Perhaps it was that, although legal, these incidents occurred in the hours of darkness!

Arthur judged that the move of all airborne activities from Writtle to Basildon in 1960 would take him too far from his sailing at Maldon, so transferred to Baddow. Writing software for Display and Data Handling Laboratories, he remained there until the mid-70s when because of a slump in contracts and staff reductions at Baddow, he transferred Basildon working in Allan Barrett’s team on the comms system for the AEW Nimrod.

In the 80s he retired early due to ill health, but, with his wife Maggie, remained very active. In his closing years he devoted himself to keeping him and Maggie, who he predeceased by only a few months, living independently at their home in Downs Road Maldon. They had no children.

Many of his former colleagues gathered at Chelmsford Crematorium on the 20th March 2006 to bid him farewell, and then afterwards at the Airadio reunion/wake at the Conservative Club in Chelmsford, at the invitation of his closest relatives. |

Veterans lost and found

Throughout the year individual committee members have come across former employees who have either complained that they had had their long service presentation and Veterans tie some years ago and then no contact from the Association, or that communications from the Association had ceased at some time in the past. There are a number of reasons for these unfortunate situations, including failure of HR/Personnel departments to pass on details of the long service employees details to the association, and failure of Veterans to notify the secretary of a change of address. Whatever the reason, if you know of anyone in this sort of situation do urge them to get in touch with Barry Powell, or pass their details on to Barry yourself. The viability of the organisation depends on a healthy membership roll.

Vimy crash landed in Derrygimlagh Bog in Ireland. This location was some 4 miles south of Clifden in Connemara and adjacent to the pioneering Marconi Wireless Station. The only means of transport to this out-post was a two-foot gauge railway. Its principle locomotive was a conversion on an Edwardian Lancia, the adaptation being undertaken by Marconi engineers at their works at Chelmsford and delivered by sea and rail to Clifden. The famous aviators had their photograph taken seated in the Lancia locomotive.

Vimy crash landed in Derrygimlagh Bog in Ireland. This location was some 4 miles south of Clifden in Connemara and adjacent to the pioneering Marconi Wireless Station. The only means of transport to this out-post was a two-foot gauge railway. Its principle locomotive was a conversion on an Edwardian Lancia, the adaptation being undertaken by Marconi engineers at their works at Chelmsford and delivered by sea and rail to Clifden. The famous aviators had their photograph taken seated in the Lancia locomotive.