Peter Turrall, MVA Chairman

Please click on the title Newsletter 2014 above to open the full document and on any picture in this newsletter to open a larger version.

Over the last nine months considerable work by the owners Bellway Homes has taken place on the Marconi Communication Systems site at New Street Chelmsford. All of the factory building has been completely demolished as well as Building 720 (the one with the wavy roof) and also the four storey building of Marconi House. The latter was riddled with concrete cancer and there was no real possibility of this remaining without extensive and costly improvements. (The accompanying aerial view was taken on 5 May 2013 by Alan Batchelor, who worked with Ted Pegram on HF Radar during the 1980s. On that date Marconi House was still standing.)

The only remaining buildings are the power house and the water tower, the latter being camouflaged in WW2 to resemble a church. The developers have just submitted plans to Chelmsford City Council for extra windows and doors to be fitted to this building. Its future use is unknown: at one time there was the possibility of an arts centre being established here, but as far as we know this has not been confirmed.

The site where the factory and other buildings were situated is now full of machinery, very high piles of earth and deep holes filled with water. In due course building foundations will be installed but it does appear this is some way off.

The front building, which has a preservation order on it, has been extensively improved, both externally and internally. The external appearance looks excellent and the gardens in front have been planted with miniature trees and other shrubs. This building will become the headquarters of the developers and already flags on our old flagpoles and other boards announcing future houses and buildings have been erected. It is hoped that the Marconi Veterans Association will be able to discuss at some future date the possibility of having some of our manufactured equipment on show within this complex, and also recording the work which was carried out here for over one hundred years.

The front building, which has a preservation order on it, has been extensively improved, both externally and internally. The external appearance looks excellent and the gardens in front have been planted with miniature trees and other shrubs. This building will become the headquarters of the developers and already flags on our old flagpoles and other boards announcing future houses and buildings have been erected. It is hoped that the Marconi Veterans Association will be able to discuss at some future date the possibility of having some of our manufactured equipment on show within this complex, and also recording the work which was carried out here for over one hundred years.

The blue plaque which announced that Marconi the Father of Wireless had his factory on this site is still in place at the front of the building and small boards with photographs are there to advise the public of the work carried out and the importance of the industry in the City of Chelmsford.

Marconi Veterans’ Association will continue to have discussions with the developers in an effort to keep alive at the site the importance of the Marconi name, the place where the manufacture of some of the worlds finest electronic equipment occurred, and to recognise that this was the site of the first commercial broadcast by Dame Nellie Melba in the 1920s.

Not a lot of new material has come in over the last twelve months, so I’ve needed to call up two backlog items which both occupy two pages each. The backlog is now all but exhausted. Interesting and relevant photos are in also in short supply. Ideally, I should have a better mix of the shorter items, those of around 400 to 500 words in length, to leaven those long pieces, together with some pictures of course, so it’s up to you, fellow veterans.

One of the longer pieces, ‘Essex Clay’, is a beautiful piece of writing by someone who is not a Marconi Veteran. Sir Peter Stothard, a former editor of The Times from 1991 to 2002, is currently editor of the Times Literary Supplement. He is the son of Max Stothard, a well-known Baddow engineer: the family lived on the Rothmans Estate – the ‘Marconi patch’ – in Great Baddow during the 50s and 60s. The article, on page 10, is an extract from Peter Stothard’s memoir ‘On the Spartacus Road’ and describes his boyhood years on the Rothmans estate.

It was first published in Granta Issue 109, Winter 2009: Work. (www.granta.com)

As in previous years, a number of letters are from correspondents seeking information about former colleagues, for research into their family history, or for the preparation of articles, books, etc. If no contact detail appears with the letter then please direct your reply or any correspondence for the enquirer to:

Barry Powell,

Secretary, Marconi Veterans’ Association,

22Â Juliers Close,

Canvey Island,

Essex, SS8 7EP;

01268 696342;

secretary@marconi-veterans.org

or to the editor, Ken Earney, 01245Â 381235; email newsletter@marconi-veterans.org

Certain items in this issue, particularly on this and the next page, are responses to letters or articles appearing in the 2013 edition which have already been posted during the last eleven months on the website. There is thus an inevitable but necessary duplication catering for those Veterans who have no possibility, or wish, to use the internet.

Note that, to avoid unnecessary repetition of the Association’s name in full, the initials MVA have in places been used.

Finally, apologies to David Emery, VJ Bucknell and Eric Walker whose contributions should have appeared in last year’s edition.

Farnborough Air Show 1952

Eric Walker, 28th February 2012

The photograph on page 13 of the 2012 newsletter reminded Eric Walker of a similar visit two years earlier.

On 6 September 1952 my wife Ann and I boarded a coach full of Marconi people to go the Farnborough Air Show, which was then a yearly event. They were exciting meetings with many new aircraft on display for the first time. It was organized by the SBAC (Society of British Aircraft Constructors) and the RAE (Royal Aircraft Establishment). With so many new and experimental aircraft there were bound to be accidents.

In those days there was no ban on sonic booms and aircraft were allowed to fly over the masses of aircraft enthusiasts. To finish his display, John Derry flew his de Havilland DH110, a twin-engined fighter designed at Hatfield, straight and low at the crowd on the hill. The plane broke up into pieces, the fuselage fell onto the runway just short of the crowd barrier and the 2 engines ‘flew’ together, with a cloud of bits dropping off. I shouted out “He’s broken-up!†grabbed Ann and dropped to the ground. The engines flew over and crashed into the crowds behind us. Many were killed and more injured, including some Marconi people. We were unhurt, just shocked, as were many others. John Derry and his colleague Tony Richards perished. These things happen.

East Ham Palais de Danse

From Doug Paynter, 12 August 2013

I first became acquainted with the East Ham Palais de Danse when I started my secondary education at Wakefield Central School at the age of eleven. It was a large building with a magnificent sprung maple floor and ornate balcony. The main use of the building was as a dance hall although other activities took place. Next door to the Palais was the Congregational Church and one of my memories is of those far of days when as a teenage church enthusiast, I was privileged to take an afternoon service from the pulpit. I can remember the vicar finishing his sermon and I had to announce the next hymn. At that moment the band next door (Sydney Anderson?) started to play ‘Somewhere over the rainbow’ as sung by Judy Garland in the film ‘The Wizard of Oz’. My foot was tapping to the foxtrot when I found myself initiating the hymn and the organ sprang into life, completely drowning the music next door. At the time I was not sure this was an improvement! Other events that took place at the Palais included marathon dances when couples competed for the longest survival. This was featured in a film starring Jane Fonda called ‘They shoot horses don’t they?’

On the outbreak of war I left the district. In 1956 I was recruited by Sir Eric Eastwood to join Marconi Research at Great Baddow. During my early days at Baddow I had to visit Marconi Marine at East Ham and on arrival I was amazed to find it was situated in the old Palais de Danse which was exactly as I remember it, the dance floor appeared to be unchanged, the balcony still ornate with red velvet pillars but used as a store for marine comms equipment.

The Established Designs Group Xmas Dinner 1964

From VJ Bucknell, March 2012

This letter provides further information about some of the missing names in the caption to the photo on page 11 of the 2011 edition.

Mike Southall is sitting on the left-hand side of the table, and is the 4th person along from the left (ignoring R Rodwell). Sitting next to him is a lady who was a draughtswoman in the DO (sorry, I’ve forgotten her name). Next to her I believe is Les Saunders. Bill Garvey is in the front of the picture next to our secretary Carole. The surname of the person seated to her left was I believe Chowdri. He was attached to Established Designs for a short while. I recognise many of the other faces but their names have left me.

Leonard Whitworth Stephenson

From K Douglas, Montreal Canada, August 2013 and amended January 2014

I was delighted to learn on-line of your association and to see mention of a distant relative, Leonard Whitworth Stephenson (1881-1970), amongst the list of deceased veterans.

As part of my family research, I have been particularly intrigued by LW’s immigration to Canada.  A passenger list indicates that an LW Stephenson left Liverpool for Montreal on 14 June 1907, and I do think that this must be Leonard Whitworth, though no age or occupation is given.  Information links him first possibly with Marconi in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, and then to the West Coast by 1912, and then, working as a government engineer, helping to establish various coastal wireless stations. He apparently retired in 1945. The last record I had found of him in England was his listing in the 1901 Census as a 19-year-old electrician, boarding in Chelmsford.

Do you hold records about individuals? And, if LW Stephenson belonged to your association, might there be any mention of his participation? (Incidentally, he seems to have visited Britain in 1919, marrying in 1922 in Victoria, BC)

The secretary replied:

The 1904 date in our records relates to the date of joining a company within the Marconi family. To qualify as a Veteran at that time, he would have had to serve for 25 years or more so would have been employed up to 1929 or beyond.

The only other information that we have is that his entry in the register was last amended in 1992 – this is usually when we are advised of a Veteran’s passing (it is quite common for this to be several years later).

There may well be service records within the Marconi Archives which are now held by the Bodleian Library under the care of Mr Michael Hughes. I would suggest that you email your request to Mr Hughes at michael.hughes@bodleian.ox.ac.uk – we have generally found him to be very helpful.

Mrs Douglas replied:

Curiously (with reference to the 25 year requirement for Veterans) from my research so far, I have found LW listed as a Canadian Federal government employee in ‘Sessional Papers for the First Session of the Twelfth Parliament of the Dominion of Canada’, 1911-1912 (on-line). He worked for Wireless Stations/Building & Maintenance’, as ‘engineer, salary, 3 m to March 31st at $125’. I’ve also found him mentioned in similar but full-time employment in 1925 and 1926, I hope to consult further such records in our National Archives in Ottawa later this month.

There are, however, gaps for LW in the Victoria Directories and Voter’s lists, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s, so perhaps LW, having retired from government work in 1945, left Victoria and did further work for Marconi at that time…

Hopefully I shall learn more as I look at other resources, and look forward to seeing your up coming newsletter.

Marconi Football Club in the 60s

From David Emery, 4 March 2012

I believe I know the identity of one of the unknown men in the second Marconi Football Club photograph (page 15, 2012 newsletter). Standing at the back with jacket and tie, third from the left, is my grandfather Reg Turner.

He joined the company in 1929 and initially worked in stores at New Street. He later worked in planning, progress, at Rivenhall (where he was superintendent), Widford and finally again at New Street as an invoice clerk with E Buck. He left on 21 November 1975. I think he was associated with the Sports and Social Club, which may explain why he appears in the photograph.

Little did I know that many years later I would follow in his footsteps when I started work at what was then Marconi Radar at Eastwood House in 1996.

I also have a question to ask – does anyone know when the fish first appeared in the cooling pond beside Marconi Road in the New Street works? Despite all the sad decay, the fish are still alive – I saw them only last week. They may be the only occupants to celebrate 100 years of the site.

That was nearly two years ago. Now, in January 2014, the cooling pond is no more.

David also sent in an enquiry via the website last March concerning any possible Marconi connection with an ex-RAF comms site on the East Yorkshire coast. The query was largely answered for him by information to be found on the Airfield Information Exchange website, see below, but if any Veteran can throw any more light on the topic he would be pleased to hear from you. (You will need to register with Airfield Information Exchange if you wish to view images or post messages there.)

Lund, East Yorkshire – email 16 March 2013

Do any Veterans know if the Marconi Company had a link with a wireless telegraph station at Lund, East Yorkshire? It is shown on mid-20th century OS maps, but the masts had probably been removed by the 1970s. A single storey building remained until fairly recently. The locals apparently refer to it as the ‘old Marconi station’.

Some Churchillian put-downs

“He has all the virtues I dislike and none of the vices I admire.â€

“I am enclosing two tickets to the first night of my new play; bring a friend, if you have one.†– George Bernard Shaw to Winston Churchill

“Cannot possibly attend first night, will attend second … if there is one.†– Winston Churchill, in response.

And welcome to 2014.

We took it easy in 2013 as my wife was still not 100%.  Then at the end of the year, we decided to upgrade our caravan to a newer, larger and better appointed one – so that’s the bulk of our holidays sorted for the next 15 years or so.  It’s still at Cromer, luckily clear of the areas that were severely damaged in December last year.

With regard to the subscription, we are pleased to maintain the rate at £6.00 per annum but, regrettably due to increased costs, we must raise the cover price for the reunion to £24.00. I am sure that you will agree that this is still excellent value for a four course meal with tea/coffee and wine.

Please note that the date of the Reunion is Saturday 5th April where our President will be Veteran Mike Thornton who for many years was with Marconi’s Aeronautical Division at Basildon. He retired from the position as Managing Director in 1994 after over 39 years service with the Company. The Guest of Honour will be Mr Ray Hagger who for many years was with Shell Mex and BP, mainly involved with retail marketing. On leaving Shell he joined a specialised training organisation and later became involved as a Pensions Liaison representative.

2014 is the centenary of the start of World War 1 and the involvement by Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company in the manufacture of electronic equipment for the armed forces through the War Department will be commemorated in the design of the coaster.

This will be the second reunion to be held at the new Club premises so there should only be some minor changes to the arrangements in the light of last year.

With regard to the name tags, there were a few problems with sending them to you but otherwise I was pleased with their reception. This year, we will produce the name tags on A4 sheets which will be at the merchandise table so you can collect your label as you enter the hall. When you order your ticket, please indicate in the box provided how you would like your tag to read. The default will be to print your name as it appears on the first line of your address label.

It is probably appropriate to say a few words about the reunion to dispel any concerns that a first time attendee may have. When you complete the application form, just tick the box requesting a ticket and indicate at which company table you would like to sit. If you have special dietary requirements (vegetarian, gluten free, halal etc.) please mention it in the space provided. We can cope with most needs – if you are not sure, please ring me. By return, well almost, you will receive your ticket.

The hall opens at 11.00am when the bar will be open and you can collect your name tag and reserve your seat at a table. We do not allocate actual places at table but only use the information from the application forms to ensure that there are sufficient places for each of the companies. If you wish to sit with a particular person or group, arrange with them to reserve a suitable number of places on a table (there are 10 places at each table) for the appropriate company. I am happy to advise you who is attending/usually attends and help you contact them. You can now relax and enjoy the reunion until lunch is served. On one of the tables there will be books containing messages from Veterans unable to attend and a list of those Veterans who have passed away since the last reunion.

If you have requested a special meal, I would urge you to arrive as early as possible, reserve your place and then let me know where you are sitting – I will be the one with a harassed expression carrying a clipboard – as I have to let the caterers know where to deliver them by 12 noon.

You will be asked to take your seats at around 12.45pm and, shortly after, the top table (including the President and Guest) take their places. On your table, for each person, there will be a commemorative coaster, menu, list of attendees and the papers for the AGM (more later). There will also be an envelope containing a strip of raffle tickets for which we would request £1.00 – someone will be around to collect this during the meal.

After a minute’s silence in memory of our founder, Guglielmo Marconi, and the grace, the meal is served. During the meal, there will be a few toasts as our President celebrates his year with parts of the Marconi organisation that have a special meaning to him.

At the end of the meal Veteran Valerie Cleare will pass on some messages from Veterans unable to attend and then the speeches start. There are only three – an introduction of the President, the President and his Guest. They are usually light-hearted and last around 5 minutes each. We have received a few comments about Veterans carrying on individual conversations during the speeches. Please refrain from this as it is very discourteous to the speaker and distracting for other Veterans. Together with a few toasts this takes us to around 3.45pm when there is a short break.

At 4.00pm the AGM commences. This usually lasts for only a few minutes and is followed by the raffle which concludes the programme for the afternoon and leaves you free to carry on the reunion.

If you have any questions, please give me a ring.

Apologies for the above to the many who regularly attend but we have had quite a few comments from Veterans saying that they would come but feared having to sit on a table with nobody they knew or having to sit through interminable speeches – if you know anyone like this, please put them right and encourage them to attend.

If you know of ex-Marconi employees who do not receive the news-letter please urge them to contact me as soon as possible. It may be that they have moved or not replied to a confirmation request of a few years ago or that they left with 21 to 24 years service and have now become Veterans by virtue of the reduction in service requirement to 21 years.

The ‘Friends of The Marconi Veterans’ Association’ has been set up to cater for anyone who does not qualify as a Veteran but wishes to be kept informed of things Marconi. Numbers are growing slowly with, currently, over 40 members, and any more would be welcome.

The ‘Friends of The Marconi Veterans’ Association’ has been set up to cater for anyone who does not qualify as a Veteran but wishes to be kept informed of things Marconi. Numbers are growing slowly with, currently, over 40 members, and any more would be welcome.

The three registers (the Main register, In Memoriam and Friends) are now published on the website so please have a look if you can and let me know of any errors.

Last year at the AGM we voted unanimously to award honorary life membership to Dr Geoff Bowles, curator of the Sandford Mill Industrial Museum, in acknowledgement of his efforts in maintaining the collection of Marconi equipment and memorabilia at Sandford Mill. At the museum open day on Saturday 27th April, International Marconi Day, I presented Geoff with a letter of confirmation, together with the association’s tie, lapel badge and 2013 Reunion coaster – see photo above.

Please note that I may be contacted at the address below. Finally, may I wish you all a very prosperous 2014 and hope to see as many of you as possible either at the reunion on 5th April or the next Open Day at Sandford Mill on Saturday 26th April (10.00am to 5.00pm).

One final note – the 2015 Reunion will be on Saturday 18th April.

Barry Powell,

Secretary, Marconi Veterans’ Association,

22 Juliers Close,

Canvey Island,

Essex, SS8 7EP

Phone: 01268 696342 (answerphone if we are out, please leave a message and I will ring you back)

Email: Secretary@marconi-veterans.org

In the Tuesday 28 January episode of this popular series, Michael Portillo visited Ransome’s works in Ipswich to hear about the production under licence of the first ever grass mowing machine designed by Edwin Budding, the Colne estuary to meet Graham Larkin of the Colchester Oyster Fishery operation, the Hole in the Wall pub in Colchester, Alderman Mechi’s experimental farm at Tiptree Hall (which is now a Wilkin & Sons farm) and Wilkin’s jam factory, then finally to Chelmsford to investigate some of our Marconi heritage.

In the 1912 New Street building he first met Geoff Bowles who explained how Marconi was the first to successfully transmit and receive over distances of several hundred metres because he, unlike the other experimenters in the field, employed an aerial and an earth connection to his apparatus: the first ever sound broadcast – readings from Bradshaw’s railway timetables and how the celebrated broadcast of Dame Nellie Melba from the Chelmsford works in 1920 sparked off the popular demand for entertainment broadcasting. Clad in the signature salmon pink jacket and green shirt Michael Portillo then went to the Sandford Mill museum to talk about the maritime applications of wireless, in particular its importance for the safety of ships at sea, with Peter Watkins, a former Marconi Marine radio officer who, as a volunteer at the museum, has been actively involved in the recreation of a working ship’s radio room and with the mounting of displays of the Walters collection of ships’ radio equipments. Peter Watkins invited him to try his hand at Morse communication – he had to admit that his keying speed wouldn’t cut the mustard.

In the 1912 New Street building he first met Geoff Bowles who explained how Marconi was the first to successfully transmit and receive over distances of several hundred metres because he, unlike the other experimenters in the field, employed an aerial and an earth connection to his apparatus: the first ever sound broadcast – readings from Bradshaw’s railway timetables and how the celebrated broadcast of Dame Nellie Melba from the Chelmsford works in 1920 sparked off the popular demand for entertainment broadcasting. Clad in the signature salmon pink jacket and green shirt Michael Portillo then went to the Sandford Mill museum to talk about the maritime applications of wireless, in particular its importance for the safety of ships at sea, with Peter Watkins, a former Marconi Marine radio officer who, as a volunteer at the museum, has been actively involved in the recreation of a working ship’s radio room and with the mounting of displays of the Walters collection of ships’ radio equipments. Peter Watkins invited him to try his hand at Morse communication – he had to admit that his keying speed wouldn’t cut the mustard.

The photo shows Peter Watkins in the radio room with, no, not Michael Portillo but the late Charles Shelton, G0GJS, of Chelmsford Amateur Radio Society. (I intended to use a screen shot from the morse-keying sequence from the programme here, but Getty Images’ licence fee said otherwise! Ed)

An appeal from Alan Hartley-Smith in the MOGS forum on 30 August 2012 for a list of supervisors at the Apprentice Training Centre in Chelmsford released a flood of reminiscences. What follows is a sample of them.

David Samways

I can only remember Joe Hillman who was there in 1957 when I started. Every lunchtime he used to have his sandwiches then lie down under his table and go to sleep for 30 minutes. That gave him the energy to berate us in the afternoons.

Jim Butterworth

I couldn’t remember the name, but the ATC supervisor still had his forty winks every lunchtime when I was there in late 1958. It was a steep learning curve for us apprentices – from 12 years at a school desk to workplace. I remember the Colchester lathes took ages to warm up on cold mornings and the smell of the soap water.

John Lancaster

I was in Pottery Lane in 1948/49 and Hillman was the supervisor. Forty winks after lunch sounds about right!

Bob Mountfort

In 1953 Joe Hillman was sleeping on a platform, under his bench, onto which he painstakingly unrolled a length of green felt. As I recall the strange smell was said to be due to a gangrenous wound on one of his legs which was bandaged. Diabetes? Or a war wound?

John L

Yes – I remember the smell, and the explanation!

Mike Plant

Regarding JH, I don’t recall him ever becoming involved in any training in our 5 or 6 months. Instructors included Messrs Whittaker – sheet metal; Lane – wireman assembly; Ted Cordery – ???; Thrift – capstans or lathes. I can’t remember who taught mills. Vertical drills too, though they could have been merged with one of the other disciplines. Others with a working memory will be able to correct me and fill in the gaps!

Colin Drake

Further (hopefully correct!) information to that sent by MP. During May to September 1954, the instructors comprised Joe Hillman – Chief Instructor (not working!); Assistant Chief Instructor – Charlie Sweetman (moved back to Dev Workshops as Chief during this period); Whittaker – sheet metalwork; Wray – wiring; Bob? Frith – lathes; Cordery – assembly; ‘Hondo’ Lane, – instrument making; Eve – milling machines; Westlake – ?

Jim Butterworth

Ye gods – I feel 50+ years younger! But what memories to remember the names of the supervisors. Apart from ‘being there’ and the amazingly fast-moving canteen queues my memories are minimal I’m afraid. I do still have and use some of the tools I made at the time; the centre punch; the scriber and the toolbox. I also still have many tools I bought at the time – the micrometer, calipers and hammer immediately come to mind. And does anyone else remember making the double screw – right hand and left hand threads with nuts to match – never found a use for it though! and the old chap wandering around with clean orange ‘ipers’ when ours got too grimy to use. Those were the days – followed by evenings working on the bikes, motorcycles and cars at Brooklands and Springfield House. Hmmm – you know you are old when you start to reminisce. Back to working out tomorrow’s swimming lessons!

David S

Ted Cordery was there for a few years because he was in Nigeria with me in 1963 and 1964. I have been trying to track him down for 18 months but got nowhere. Anyone know of him?

John Tarrant

In addition to the names already mentioned, I would also like to add the name of Johnny Cooper, who in 1956/57 was in charge of the capstan lathes. Sadly he passed away during that time. I well remember the double-ended screw and nuts with left and right hand threads. I spent a lot of time trying to help salvage some of the disasters that occurred producing them, and re-grinding screw cutting tools, during the time I was seconded for about six months to assist Freddy on the lathe section when, in the absence of Johnny Cooper, the capstan lathes were added to his section. Colin Drake mentions him as Bob Frith, which is probably correct, but I remember him as Freddy Frith. In addition to Joe Hillman, how about adding the names of Frank Wilder and Bob? Hitchins (or Hitchens) who were both involved with apprentice training, and resided in what I remember as the education office on the mezzanine floor above Joe’s office.  For any of you that were ever posted to Waterhouse Lane you will also no doubt remember Ernie, who ran the small sheet metal work section that was supposed to add to the skills gained from Frank Whittaker in the ATC, and whose main objective seemed to be to assist those under his wing to produce what he called a ‘proper’ tool box, that was bigger and better than the standard ATC product. I still have one of these much improved Waterhouse Lane versions, which is in regular use. Hope that this might ring a few bells for some of you. (The toolbox shown is one of the standard ATC variety belonging to Ray Binning.)

For any of you that were ever posted to Waterhouse Lane you will also no doubt remember Ernie, who ran the small sheet metal work section that was supposed to add to the skills gained from Frank Whittaker in the ATC, and whose main objective seemed to be to assist those under his wing to produce what he called a ‘proper’ tool box, that was bigger and better than the standard ATC product. I still have one of these much improved Waterhouse Lane versions, which is in regular use. Hope that this might ring a few bells for some of you. (The toolbox shown is one of the standard ATC variety belonging to Ray Binning.)

Jim Butterworth

As we have moved upstairs – going up to the Education Office usually brought news I didn’t want to hear. However I can remember attending the Workers Educational Association meetings; can’t remember anything about them now, or if I actually learnt anything! But how do you remember all those names so many years on? I can’t remember what I had for lunch yesterday!

David Samways

I can’t believe you have said that. The only reason apprentices moved upstairs was to view Jackie! Many folks, if they agreed of course, would agree!

Brian Kendon

No one seems to have mentioned Mr Watts who was Mills and Drills in my time at the ATC (1949/50). I have fond memories of being one of the few who managed to operate the tapping machine without breaking 6BA taps in the hard brass work pieces. Not to be forgotten was the reaction of all to the sight and sound of a mill table ploughing into a surrounding newly constructed health and safety cage out of control of a young man not suited to the workshop environment. Those were the days.

John Lancaster

I remember Mr Watts very well – he couldn’t understand why I found it so difficult to sharpen a drill correctly! I can see his face now, when he said – ‘do it again, Lancaster’!

Colin Drake

And yet another memory, the capstan – ‘turrets’ were taught by Johnny Cooper in ‘54

Alan Matthews – ‘Matty’

I went into the Training Centre in 1953. Charlie Sweetman was the chief instructor.

I was making a ‘Home Office’ extractor to pull the flywheel from its taper on my Douglas Motorcycle and needed a large diameter (bigger than half an inch) bolt to go into a tapped hole in the centre of the extractor. So I made out a stores warrant for it and asked Charlie Sweetman to sign it. “What the hell is this for he asked?†– so biting the bullet I told him and received a right *******ing, after which he signed it!!! The tool worked fine by the way and if I still had it I suppose I could donate it to Mike Plant who has a Douglas still.

When working on the Mills section, which was in line with Joe Hillman’s open door, I left a very big shifting spanner on the nut on the end of the mill shaft. Went away and then came back pushed the GO button on the mill which proceeded to start and throw the spanner with one bounce through the door into the office. Another lesson learned the hard way.

I think Mr Watts was a small man who instructed on centre lathes and was always amazed that he could work looking down at the job with a fag in his mouth. My final test with him was to make a spindle with a three start Acme thread at each end – one end left handed and the other right. Then a suitable big knurled nut had to be made to fit each end.

I think I struggled for about a week before I had finished, with much scrap metal created, before I took it to him for inspection. He put the nuts on and shook it. “Well that’s what we used to call a ‘rattling good fit’ in the trade but I suppose it will do†he said. But I think that the skills they taught to us young green lads in a few months were really quite amazing.

Jim Butterworth

The apprentices training was certainly an unforgettable experience for all of us. Many skills were learnt which have stood me in good stead over the years. Coming to the ATC from 12 years of school, 9am-4pm with a long lunch break, ensured we slept well; I can remember going to sleep in the middle of a conversation and waking up 8 hours later in time for a ridiculously early (to me) breakfast at Brooklands. And then Mid-Essex courses in the evening when you were already tired out and really only wanted to sleep.

As well as the machinery already mentioned, remember the test pieces we had to make using waxed thread – every turn equi-spaced and all the knots in a straight line? And repeat assembly of small mechanisms – how many hundred in a day? And then Transmitter Test – real work at last!

I forget the names but I shall never forget the experience – with grateful thanks to Marconi and their long-suffering instructors.

The 77th annual Veterans’ Reunion took place last year on Saturday 20th April. Our President for 2013, in recognition of his tireless efforts on behalf of the Marconi Veterans’ Association and keeping alive the name and memory of Marconi, was our chairman, Peter Turrall. Unfortunately, due to a temporary health problem, he was unable to attend the union.

The toast to the President was proposed by our Patron, Veteran Robbie Robertson, who opened by saying that regardless of any time limit that Peter might have set for his contribution he was going to take the time needed adequately to say what needed to be said.

Peter joined Marconi in 1951, eight years before Robbie. The fourth floor of Marconi House then was hallowed ground belonging largely to Broadcasting Division; humble Communications Division guys could only visit the top floor with permission, to seek knowledge and wisdom on the mysteries of broadcasting. He has lost count of the number of times that Peter, the source for him of all information on TV studios, had pulled him out of the holes he’d dug for himself in the early days of his involvement in broadcasting: through the years it often seemed he was being rescued from someone or something, once notably during a visit to South West TV in Plymouth. Of the many things they did together, one of the most memorable for him of Peters’ many achievements was the MCSL Agents Conference around 1986. Representatives from around 40 countries attended; thanks to Peter’s splendid organisation, none of the expected disasters occurred, or at least only nearly!

Robbie spoke of Peter’s incredible contribution to the Marconi Veterans’ Association. An active member of the committee for around 25 years, most of which was either as vice-chairman, or for the last several years, as Chairman, with many hours spent in committee meetings and countless further hours implementing decisions made at the meetings. Peter has campaigned tirelessly for all things Marconi; Chelmsford owes him a debt of gratitude for his efforts in the public arena, on a mass of activities far too numerous to list, for instance, major contributions to Mencap in Essex; his involvement in the life of Chelmsford Cathedral, and his current efforts regarding the New Street site redevelopment.

Robbie closed by saying that we were all honoured, and grateful, that Peter has agreed to be our president for 2013. We thank him for this, and we wish him all that is good in his presidential year.

In a recording played to the Veterans Peter Turrall apologised for not being able to be present at the reunion. He then went on to talk about the importance of the history of the company, mentioning Bill Baker’s official history which covered the period from the company’s founding until 1950. When he was asked by Sir Robert Telford to clear out his office, he was told that all senior staff had been asked to commit to paper the story of their operations, designs and stories concerning the installation. As a result a large amount of material was gathered up and handed over to the Sandford Mill museum. He appealed for any veteran with memories to contribute to commit them to paper, or tape, and pass them on to the secretary, Barry Powell, or to Alan Hartley-Smith (ref Alan’s appeal on this subject in last year’s newsletter, page 5, also this edition pages 6 and 13).

Regarding Marconi House in Chelmsford, Peter is attempting to maintain good relations with Bellway Homes, the owners and developers of the New Street site with the aim that at some time in the future there will be a room in the building dedicated to Marconi where we might display some of our artefacts. He spoke about the difficulties of getting Chelmsford Borough (now City) Council to recognise the reputation and tangible benefits that Marconi and the other great industrialists brought to Chelmsford, and that those efforts must be maintained.

His final theme was the enjoyment derived from 48 years serving under nine managing directors – he got on very well with eight of them, but under the ninth he felt he qualified for the ‘I survived Glasgow’ badge. He recalled one or two high points in that career. The first, attending an exhibition at the IBC in a London hotel and showing, at lunchtime when only one other colleague was with him on the stand, an unknown gentleman and lady the various equipments on display, only to discover at the end of their visit that he had been speaking to Sir Arnold Weinstock. The second highlight was to win his biggest order ever, much celebrated back in Chelmsford, from the Egyptian broadcasting organisation for OB vehicles, cameras, transmitters telecine equipments etc. He concluded by appealing again for veterans to commit their memories to paper.

Our Guest of Honour this year was Mr Jonathan Douglas Hughes OBE DL who is a senior partner of Gepp & Sons, solicitors in Chelmsford and Under Sheriff for the county of Essex. In his speech he concentrated on his work as Under Sheriff. This is very much a legal role and, in particular, he has on his staff four bailiffs. He is not involved in the day to day collection of small dues but becomes involved in major recoveries.

As an example he recounted the story of a Boeing 707 presidential jet that was flown into Stansted from Africa with the president’s family. The owner of the aircraft (not the president or his government) required payment of the leasing dues, and others required payment for the fuel. As a result the aircraft was seized and the Under Sheriff ultimately disposed of the aircraft to recover as much money as possible.

In a brief address during the AGM, Alan Hartley-Smith, against the background of his article in the 2013 newsletter, outlined the contacts made with the BAE Heritage Committee and Heritage Manager Howard Mason with a view to establishing how Marconi heritage aims can be integrated into BAE Heritage policy. BAE is already involved in providing assistance in transferring a S600 radar at Bushey Hill to the RAF Air Defence Radar Museum at Neatishead in Norfolk. The principal aim is to establish a physical Marconi Heritage Centre in Chelmsford, possibly connected in some way with the redevelopment of the New Street site. He appealed for ideas as to how this centre might be used and funded – meetings, exhibitions, Marconi-related lectures etc. The full transcript this appeal and all the reunion speeches are available on the website. (Please also see below AH-S’s report of the Marconi Heritage Group activities for the past year.)

The editor relayed an appeal from the Essex Record Office for volunteers to be available for assistance with the examination, cataloguing and indexing of the Marconi photographic archive in ERO’s possession, a project that is to be the subject of a Heritage Lottery funding bid by ERO. Owing to the similarity of its aims with those of the Marconi Heritage Group reported below, ERO is to liaise with the group with a view to preparing a combined bid encompassing the aims of both.

A reminder that this year’s reunion is held on Saturday 5th April, and in 2015 it will be on the 18th April.

Alan Hartley-Smith

A lot of activity has been undertaken by the Marconi Heritage Group in the past year leading to very positive outcomes, with the result that we are now seeking to set up a charitable trust to carry forward negotiations.

A lot of activity has been undertaken by the Marconi Heritage Group in the past year leading to very positive outcomes, with the result that we are now seeking to set up a charitable trust to carry forward negotiations.

Following the presentation by BAE at the 2013 Reunion there has been continuing participation in the Heritage Product Committee. This led to a significant action in the form of the donation of an S600 radar to the RAF Air Defence Radar Museum at Neatishead, which is currently being installed ready for public exhibition (photo – right). Also Marconi is featured in the prestigious 2014 Heritage calendar. Ongoing are discussions with the aim of achieving the creation of a physical heritage centre.

Locally we have participated in two major events: the Essex Record Office conference on Essex’s Industrial Archaeology in July, at which Professor Roy Simons gave a presentation ‘Marconi the Father of Wireless’ which roused a lot of interest, and the ‘Changing Chelmsford Ideas Festival’ in November. We took part in three activities: Marconi’s Wireless Telegraphy Workshop hosted by Geoff Bowles from the Sandford Museum, in the Library atrium; ‘Imagining Marconi’s and Hoffman’s industrial past – The Frederick Roberts Archive’ hosted by Anglia Ruskin University; Marconi – Then and Now, a meet-and-greet session hosted by the Marconi Heritage Group in the Library atrium. Display panels covering the company history were provided by the Essex Record Office, where a large number of people with personal and family Marconi connections met our team. We recorded many personal memories and received great support for better recognition of Marconi by the city.

From this latter event there have been follow-up meetings involving other parties interested in preserving and promoting heritage in Chelmsford. One of these relates to the effort to find premises for a heritage centre, which is ongoing, with possibilities including the New Street site and more recently the original Marconi factory in Hall Street. It is as yet too early to make any positive statement but there are hopeful signs of progress.

During the year there have been several associated events of interest, in particular a presentation in Bedford by Professor Francesco Marconi about his grandfather’s early history, at which we made contact and received a promise of support. At the ERO conference the formation of a new Essex Industrial Archaeology Group was announced and we are now working with them.

Much progress has been made with populating the online wikis, in particular those associated with communications, for which there are now extensive entries covering broadcast and line systems, television, marine and avionics.

A major current activity is to have the considerable contribution made by wireless in the operations of all three armed services during the First World War properly recognised during the commemoration activities being mounted over the next four years, to which end we have joined the First World War Centenary partnership being coordinated by the Imperial War Museum. We are seeking input from as many sources as possible and would welcome any information from the members of the MVA.

We will be organising events as part of the 2014 Chelmsford Ideas Festival, which is provisionally timed to run from 20th October to 2nd November. See also Stop Press on page 11

Peter Stothard

Essex clay could be like living flesh or a cold dead wall. We could punch it, climb it, cut it, try to mould it, try not to offend it, but the clay was permanent like nothing else. Half a century ago, behind the back door of a semi-detached house on the Marconi works estate, a mile from Chelmsford, were hundreds of slimy-sided cubes of this clay, newly cut by machines, soft but indestructible, leaden red by day and looming brown by night, an amalgam that at a child’s bedtime might be an Aztec temple or an ancient Roman face or a Russian.

Ours were homes built in a hurry, dug out of a butcher’s farmland below a giant steel aerial mast that had been erected against the Communists as soon as the Nazi threat was past. The mobilization of men and material to watch for Cold War missiles was as demanding as the hot war in which my father and his engineering friends had learned their craft. In the Rothmans fields of Great Baddow village, beside a town that already boasted the title ‘Birthplace of Radio’, we became part of an instant works community of families whose fathers understood klystrons, tweeters and ‘travelling-way tubes’ for the long-distance radar that kept the enemy at bay.

Every man I knew then understood either about the radar that saw things far away in the dark or about the various electric valves that were its eyes. There was a residual wartime spirit, an appreciation of values shared; and also a rising peacetime ambition for new values, new houses, holidays and televisions. As well as helping to defend British prosperity against hostile objects in the sky, we were supposed to share in it, creating a haven of high education, a science park, even an Essex garden community in which the clay cut to make the foundations of 51 Dorset Avenue might one day grow cabbages, fruit trees and flowers.

There were many advantages to life on these company streets. Almost everyone, for example, had a television set. Almost everyone’s father could make his own model if he wished. Ours had no polished cabinet (my mother’s woodworking came only later) and its twinkling diodes were slung along the picture rails and around the back of the sofa. But when we wanted a better picture, the contrast of our black and white could be improved from the first principles of the cathode ray. To make the most of The Billy Cotton Band Show, a massed expertise could be deployed, from as far afield as Noakes Avenue, the outer limit where Marconi-land ended and Essex farming returned.

The houses were so alike, and the food in their cupboards so absolutely alike, that it hardly mattered where on the estate we fed our pet pond creatures or ate our tea. Most boys had the same-shaped box room for their den, an unusual cube that contained within it another cube, not much smaller than itself, in which the inner supports of the staircase were held. A sawn-off end of a radar monitor was so perfect for newt-keeping that every boy who braved the ‘bomb-hole’ pond in the ‘rec’ had one of his own. Break the glass and there was always a replacement the next night. All groceries came from the same dirty-green single-decker coach of ‘Mr Rogers’, a silent ex-soldier who piled his fruit and vegetables on either side of the aisle where the seats had been and twice a week toured the avenues from Dorset to Noakes to sell cereals, sugar, flour – everything that the gardens might one day produce but did not yet.

Books were universally rare. There were five at 51 Dorset, the brightest-coloured being a sky-blue edition of ST Coleridge, the title printed in such a way that for years I thought that the poet was a saint. Next to it sat a collected Tennyson, in a spongy leather cover, half bath accessory, half one of the then new and exciting table-tennis bats from Sweden. There was my Yorkshire grandfather’s copy of the second half of Virgil’s Aeneid, with the name B Stothard, in a firm, faded script, inside the flyleaf. I have that one here with me now. On the shelf below was a cricket scorebook in which someone had once copied improving philosophical precepts, and beside that, The First Test Match, a slim, slate-green hardback which alone looked as if it had been read.

This was a community of algebra and graph paper. Mathematics was the language of choice. Contract bridge was the nightly recreation. My curly-haired, smiling father had a brain for numbers that his fellow engineers described as Rolls-Royce. Notoriously, he did not like to test it beyond a purr. In particular – and this was unusual in a place of intense educational self-help – he did not care to inculcate maths into his son. This was a task which he had recognized early as wholly without reward. Max Stothard would occasionally attack the mountain of clay in his garden but never knock his head against a brick wall. He was nothing if not blissfully relaxed.

Like most of our neighbours, he had learned about radar by chance, in his case while becalmed for the war years off West Africa on a ship called HMS Aberdeen. He had bought red-leather-bound knives for his mates back in the Yorkshire-Lincolnshire borderlands; he had sent postcards of Dakar’s six-domed cathedral to his strictly Methodist mother; he had never fired a hostile shot except at a basking shark. And when he had needed something else to do, he chose to watch the many curious ways that waves behave in the air above the sea, turning solid things into numbers. That was how he spent most of the rest of his life, in the south of England instead of the north because that was where the radars were made, quietly reasoning through his problems on his ‘bench’ in the Marconi laboratory and in an armchair at home, spreading files marked ‘Secret’ like a fisherman’s nets. He earned £340 per year, as my mother and I discovered when he died. Secrecy about earnings was always an obsession, although everyone was paid much the same.

The Rothmans estate was based on a bracing sense of equality and a suffocating appreciation of peace. Although most of our fathers felt they had a part in this great military project of the future, rarely can so massive a martial endeavour, the creation of air defences along the length of Britain’s eastern coast, have been conducted in so eirenic a spirit. Not even the Bournville chocolate workers of Birmingham, the group best known then for living together in a company town, could have demonstrated such a Quaker appreciation of calm. The fighting war was absolutely over. The new business was civil, work carried out with civility above all else, work that would keep us safe and increase our prosperity as the politicians promised. And because everyone was in it, everyone was in it together.

That was the constant message of Miss Leake, our doughty headmistress at Rothmans School, whose doctrine of ‘excellence and equality’, delivered in her severest voice, was adapted only slowly to the gradually advancing evidence of differences around her. There were certain girls with vastly superior proficiency at maths; but certain boys could freely pervert the spirit of Rothmans peace in a greater Rothmans cause, designing missiles and fighter planes to crash Pauline Argent and Anne Spavin back to earth. For our first two years Mrs Sheffield reassured us repeatedly that we were all much the same; but eventually and inexorably, when we were aged seven and in the empire of Mrs Maloney, those of us who counted badly had to be separated from those who counted well. Those who could not sing were called ‘groaners’ and told to wait outside the door; and those who preferred Virgil’s stories to vulgar fractions were reluctantly allowed to write fiction for our homework, as long as it was science fiction.

My father was not at all worried about my being a ‘groaner’ (he listened to no music himself at all and was especially offended by the violin and the soprano voice) but he was faintly sad about my missing number skills. Numbers were the key to advancement. Physics was the first step to a working future, a future in paid employment in a world which itself worked well. Many of my friends with no aptitude at all for figures – who could draw a beautiful anti-Pauline-Argent plane but never match her equations – were pummelled on to numerical paths. How, asked our neighbour on the other side of the clay mountain, could anyone pull themselves up by any other route? It was hard to find anyone who would argue with this doctor of metallurgy from the northern steel lands of Scunthorpe – about that or about anything much else except bidding conventions in hearts and spades and the best way to see things that dared fly low in the sky.

At the same time there grew among us the gradual acceptance of other differences. Ours was only in part a works estate in the tradition of the Birmingham chocolatiers and the Wirral’s Port Sunlight. It was becoming a place for the upwardly mobile at a time of restless mobility. So there were questions. Were the engineers’ families of Rothmans Avenue, Dorset Avenue and Noakes Avenue quite as much the same as first appeared? Did the more brilliant scientists live in Rothmans, the more managerial in Dorset, the more clerical in Noakes? Were they richer in Rothmans and rather poorer in Noakes? Did the ‘Millionaires Row’ houses by the school gates really have four bedrooms? Whose kitchen had less Fablon and more Formica? Should Marley floor tiles be polished? And where exactly did everyone go on holiday?

Summer was the great unequalizer. On the North Sea coast, only thirty or so miles away, the skies were known equally to all masters of air defence. But the beaches beneath were crisply divided. Clacton, Walton and Frinton were never the same. We always went to Walton-on-the-Naze, the middle town of the three, the one which had the widest concrete esplanades where children could ride bikes. Clacton?on?Sea was south of Walton and had slot machines and candyfloss booths where ‘other people’ could waste their money. North of Walton was Frinton-on-Sea, which had no candy-floss, no caravans (we always stayed in a caravan), no fish and chip shops, not even a pub, just Jubilee gardens and what was known, only by warnings not to walk on it, as ‘greensward’. Did Rothmans Avenue families prefer Frinton? By the time of my eleventh birthday in 1962, it sometimes seemed that they did. Our Marconi estate was small, confined and had only one entrance to the world. Once inside it we could always roller-skate through the class lines. On the coast, it was an impossible walk, and even an awkward drive, between three neighbouring towns that seemed built deliberately to show how different from one another we might be.

Summer was the great unequalizer. On the North Sea coast, only thirty or so miles away, the skies were known equally to all masters of air defence. But the beaches beneath were crisply divided. Clacton, Walton and Frinton were never the same. We always went to Walton-on-the-Naze, the middle town of the three, the one which had the widest concrete esplanades where children could ride bikes. Clacton?on?Sea was south of Walton and had slot machines and candyfloss booths where ‘other people’ could waste their money. North of Walton was Frinton-on-Sea, which had no candy-floss, no caravans (we always stayed in a caravan), no fish and chip shops, not even a pub, just Jubilee gardens and what was known, only by warnings not to walk on it, as ‘greensward’. Did Rothmans Avenue families prefer Frinton? By the time of my eleventh birthday in 1962, it sometimes seemed that they did. Our Marconi estate was small, confined and had only one entrance to the world. Once inside it we could always roller-skate through the class lines. On the coast, it was an impossible walk, and even an awkward drive, between three neighbouring towns that seemed built deliberately to show how different from one another we might be.

My father was a typical Rothmans engineer of his time, in every respect except in certainty that his was the right path. That was his grace and glory. He never stopped me preferring stories about science to the understanding of what science actually did. He read the fictions that I wrote about my manufactured hero, Professor Rame, without complaining directly to me that there was no point in any of that. He did not much like the Coleridge and the Tennyson being on hand. But he did not take them away. He himself liked to see people as electro-machinery, as fundamentally capable of simple, selfless working. It was simpler that way. But he never imposed the company line. His own mind was closed to the communications of religion or art. His favourite picture then was a photograph of Great Baddow’s tribute to the Eiffel Tower. But his passions for moving parts, moving balls and jet streams in the skies over air shows did not preclude an acceptance of others’ passions. He was a pleasure-seeking materialist – in a company estate where those were the prevailing values and the predominant aspirations. Materialism in those days was a means of science, which he loved, not of extravagance, which did not exist, nor even of shopping, which he would barely tolerate. It was the successful basis of a contented, comfortable life.

John Wright, ex Electro-Optical Surveillance Division, Basildon

In the early 80s, Baghdad was one of the safest cities on the planet. It was also remarkably civilised considering Saddam Hussein was fighting Iran and had an iron grip on the country, keeping it isolated from external influence. Western dress was acceptable – one rarely saw a burqua – and you could sit by the Tigris and drink beer at the riverside bars. Saddam of course was everywhere. His picture was in every commercial establishment, on huge posters in the street and the evening television programme was one long propaganda show – Saddam the military leader in a tank inspiring the troops, compassionate Saddam in a hospital with the wounded and then his cameo performance in a story. Some poor person gets robbed or beaten when he is rescued by a mysterious stranger who keeps his face hidden until the end when, surprise, surprise, it’s Saddam again!

I first went there with our marketing man on a two-week sales demo trip with one set of airborne surveillance equipment. Waiting for our equipment to come out of customs (sound familiar?) gave us time to acclimatise to a Baghdad with a chronic shortage of electricity. It was three months after the Israelis had flattened the local nuclear power station which meant we only had electricity for an hour a day – bad enough in itself but worse when you don’t know which hour. Torches were the order of the day and try and make sure you are not covered in soap in the shower when everything dies. Without lights, the restaurants resorted to candles and Flambé became the ‘in’ dish – lovely in summer with no air conditioning. Anyhow, eventually we got our equipment and were taken to the helicopter base at a place called Abu Ghraib (we always wondered what the nearby high security building was!). The base housed the VIP squadron and the Colonel in Charge, trained by the RAF, was Saddam’s personal pilot – probably not the safest of jobs.

By this time we had already lost nearly a week from our time schedule so we had to ask to work beyond the normal one o’clock finish to meet our timescales. This caused consternation amongst our hosts as they didn’t do any catering on the base and they were in danger of not being able to provide the traditional Arab hospitality at lunchtime. A man was despatched and he came back with some rather nice meat, salad and bread. A table was laid out in the middle of the hangar and we were invited to eat while all and sundry watched – to refuse would have been an insult. By six o’clock that evening sickness and diarrhoea had brought us down – we later found out that the food had come from a dodgy roadside stall. Eventually however, we got the equipment installed and started flying. The idea was to demonstrate how we could see things miles away etc, but we soon found that the heat haze put paid to all that. So we stooged around and just videoed anything vaguely interesting: this seemed to satisfy the Air Force and they eventually placed a substantial order with Basildon.

The marketing man left and shortly after this, after arranging for the return of the equipment, I returned to UK, the first 1000km by taxi. With only Iraqi and Jordanian planes flying out of Baghdad, flights were hard to come by and the alternative was a ride in a large old American gas guzzling taxi. A price is agreed and off you go across the desert on a largely straight road at 130 km/hour regularly passing the burnt out wrecks of less fortunate high speed taxi trips. Half way between Baghdad and Amman, at a stop in the middle of nowhere, the driver starts talking of extra money for petrol. This is the cue to quickly get back in the taxi, strap yourself in and then tell him the Ts and Cs of the journey do not include extras for petrol.

The marketing man left and shortly after this, after arranging for the return of the equipment, I returned to UK, the first 1000km by taxi. With only Iraqi and Jordanian planes flying out of Baghdad, flights were hard to come by and the alternative was a ride in a large old American gas guzzling taxi. A price is agreed and off you go across the desert on a largely straight road at 130 km/hour regularly passing the burnt out wrecks of less fortunate high speed taxi trips. Half way between Baghdad and Amman, at a stop in the middle of nowhere, the driver starts talking of extra money for petrol. This is the cue to quickly get back in the taxi, strap yourself in and then tell him the Ts and Cs of the journey do not include extras for petrol.

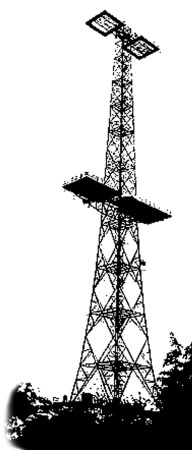

A year later, the editor went off to Baghdad with three other specialists to start the installation work and I joined them a couple of weeks later We spent the next few weeks fitting out and certifying the first helicopter and our mobile receiving station, a remotely steerable antenna/receiver on top of a 100 foot mast (see right). We had both received instruction on the erection of these masts which required nifty work with winches and some sturdy stakes in the ground for the guy wires. Fine in the UK but a bit iffy in desert sand and once it had been erected at Abu Ghraib, the first thing we did as we arrived for work every day was to look to see if it was still standing.

Having completed the fitting out and certification of the first helicopter, the team apart from me went home. Many of us have grand plans of visiting exotic places whilst returning home but usually when the time comes we are just glad to get on the first, fastest direct flight home. The editor is the exception – he actually does it and on this occasion was last seen disappearing into the Jordanian desert on a camel (the reality was a pony, but camel sounds more appropriate somehow – see picture below) to witness the dawn sun rising on the ancient city of Petra.

Nothing much happened at Abu Ghraib for a couple of weeks and then there was a request for a two-week training course to prepare a team to do some battlefield surveillance. Seven NCOs and a flight lieutenant duly turned up and I started instruction. Cameras, lenses, zoom, focus, transmitter on, transmitter off – it’s not too difficult and operating in the helicopter just needs a bit of practise. Putting 100 foot towers up and aligning them is another matter. The mast was raised up to its full 100 feet and had been lowered back down 20 feet and I was beginning to feel hopeful that the team had mastered it when a winchman started winding one of the guys too hard and pulling the mast to one side. And when he was shouted at to stop he just panicked and winched harder. Racing towards him, I suddenly realised that the mast was doomed, changed direction and dived under a lorry as the mast broke and collapsed around us. Being brainwashed by GEC, all I could think of at the time was ‘who is going to pay for this’. Fortunately, the antenna landed in sand and after some straightening and reassembling it worked again. Some sections of the mast were broken but we were able to use it up to sixty feet – a good job as it was the only one in-country at that time. Anyhow, the course was completed and everybody passed, including the flight lieutenant who always sat facing the opposite direction in the classroom, smoking a cigarette and not listening to a word to show his contempt. I don’t know how he passed but leaving the exam room unattended may have helped.

Nothing much happened at Abu Ghraib for a couple of weeks and then there was a request for a two-week training course to prepare a team to do some battlefield surveillance. Seven NCOs and a flight lieutenant duly turned up and I started instruction. Cameras, lenses, zoom, focus, transmitter on, transmitter off – it’s not too difficult and operating in the helicopter just needs a bit of practise. Putting 100 foot towers up and aligning them is another matter. The mast was raised up to its full 100 feet and had been lowered back down 20 feet and I was beginning to feel hopeful that the team had mastered it when a winchman started winding one of the guys too hard and pulling the mast to one side. And when he was shouted at to stop he just panicked and winched harder. Racing towards him, I suddenly realised that the mast was doomed, changed direction and dived under a lorry as the mast broke and collapsed around us. Being brainwashed by GEC, all I could think of at the time was ‘who is going to pay for this’. Fortunately, the antenna landed in sand and after some straightening and reassembling it worked again. Some sections of the mast were broken but we were able to use it up to sixty feet – a good job as it was the only one in-country at that time. Anyhow, the course was completed and everybody passed, including the flight lieutenant who always sat facing the opposite direction in the classroom, smoking a cigarette and not listening to a word to show his contempt. I don’t know how he passed but leaving the exam room unattended may have helped.

And so, off we went to Basra. I flew down in the helicopter with the surveillance turret fitted. Flying over the desert requires a different technique due the strong thermals – the helicopter soars and swoops using them as opposed to battering through them, so it is relatively slow. We were forced to land once at a remote radar station to avoid a sandstorm – the officer i/c proudly reciting the names of all the then current Manchester United team to me when he found out I was English. Then off again for the best part of the trip, flying over the southern Iraqi marshes, with spectacular views of the Marsh Arabs who live in ornately woven reed houses on floating reed islands.

As for Basra, we put up our 60 foot mast and the helicopter went off with one of the trainees to video the battle where Iraq lost Khorramshar to the Iranians. The results were pretty useless, the helicopter was keeping its distance, the operator didn’t know where to look and the combatants kept themselves hidden in all the dust which was being stirred up. And so interest was lost, I was despatched back to Baghdad, this time in a Russian MIL8 helicopter – crude but roomy. Then back to UK, this time by air from the brand new Baghdad airport. It hadn’t quite sorted itself out and tended to over issue boarding passes so when you were due to board, you milled about by the departure gate and when this was opened, you raced across the tarmac to the aircraft, found a seat and strapped yourself in – women and children first might be OK for the Titanic but not Baghdad Airport!

Many months later, when all the equipment on the contract had been delivered, the editor and I returned to commission it and complete the contract. This time, everything had moved to a big military establishment at Taji, north of Baghdad. Fortunately, we were able to travel daily from the luxury of the Sheraton Hotel in Central Baghdad. It was at the Sheraton that I discovered the gourmet side of the editor. Nearly every evening a different nationality theme buffet was available where he had to sample every dish, which in total amounted to at least 3 dinner plates full – and he didn’t add a pound to his weight!

Our visit was in February and even on a sunny day we wore woolly-pullies to keep warm. We shared the hangar with Russian built Hind gunships fitted with multiple rocket launchers which were used effectively against the Iranians when they carried out their first world war tactics of charging en masse across open ground. There were no workshop facilities available and we were reduced to carrying out delicate adjustments to cameras, lenses, gyros etc on the helicopter with power coming from a huge, noisy diesel ground power unit belching fumes only six feet away.

Finally it was time for us to leave for the last time. The support team we had trained seemed genuinely sorry to see us go. Ken mentioned taking back some local cake delicacies to UK so they gave us what seemed like the total output of the local bakery. I was not surprised as, apart from the odd hardliner, the Iraqis were very nice people and I feel really very sorry for their troubles since our ill-advised venture with George W.

Alan Hartley-Smith

There is to be an Essex County Council event in Hylands, Chelmsford on 14th September – we plan to be represented, and MHG has been registered in the First World War Centenary partnership being coordinated by the Imperial War Museum – see http://www.1914.org/partner/?id=AM463539 for our entry.

Tim Wander has put together a booklet about Marconi involvement with all three armed services; I will be incorporating copy and pics from this for the events and in a new website www.marconiheritage.org which is still under construction. Veterans who have relevant information about their own or family involvement are invited to make contact with me.

Eric Walker, formerly Airadio, Basildon

In the 2007 newsletter I reproduced an extract from a much longer piece by Eric Walker – for all of his Marconi career an Airadio man – which focused on some of the less serious aspects of the life of the avionics engineers inhabiting the Writtle huts in the 50s. Mike Lawrence, who served in the DO at Writtle and for a while at Basildon, expanded Eric’s original article, written in 1998, with additional material and turned it into a hand-crafted booklet with a very limited production run. Eric and Mike both had copies – Mike is sadly no longer with us – and other copies went to the Writtle village archivist and to the Sandford Mill Museum. It is well worth reading in its entirety, and we are endeavouring to make it accessible on the website.

The photo below shows the Lawford Lane site sometime between 1948 and 1956, the period in which the Lancaster airframe was resident there. The photo at foot of page 17 shows a view of some of the huts.

This extract looks at the day to day life of the Airadio people in their Writtle times – working conditions, getting on with one another, pay, perks – or lack of, and so on. It was written in 1998, but would anyone in work today, looking at Eric’s comments on how it he viewed things in ’98, perhaps raise a wry smile? Do graduates starting to climb the seniority ladder expect to get an office, as was the norm in ’98? All workplaces are much more open plan these days.

Life was made cheerful by the morning and afternoon arrival of Fred Hazel and his tea urn. He was usually accompanied by his mate Stan Porter, a very quiet man. Fred also swept out the huts and could be regarded as an early proponent of recycling as he sprinkled his used tea leaves to keep down the dust! In the early part of the 50s food was provided by Ella Walden in the canteen hut. Later, as the staff numbers grew, we took over her hut and people made their own arrangements for grub.

It might be of interest to today’s new graduates that I joined in 1951 at £350 per year. So my take-home pay was, after ‘Standard Deduction’ about £25 per month. To my surprise and delight I also received £2.5.5d (£2.27) per month supplement! We didn’t have a minimum wage in those days – so I suppose it was a state incentive to encourage firms to provide apprenticeships. When I moved on to staff conditions in March 1952 I received £500 pa. It took me 4 years to double this pay rate. In the whole of my 40 years with the company I never received a single penny for the enormous amount of overtime I worked then, and throughout the rest of my time. Staff salaries managed to increase just ahead of the overtime payment limit! I think the criterion was that overtime was only for hourly paid workers. Staff were expected to work whatever hours were needed to get the job done.

Another point of comparison, then and now, is the working environment. Nowadays as soon as graduates start to climb up the seniority ladder, they hope to get an office or at least a boxed-off cubicle to themselves, with desk, filing cabinet, telephone, a chair, personal computer etc, etc. Our Green Satin team worked in a wooden hut with benches and stools. You didn’t even have a dedicated area of bench although before long the hardware took a fairly static location so a work pattern was formed. The only office was a partitioned-off bit, open at the top where Geoff Beck worked. It was necessary because he had ministry and company visitors. We took the view that it maintained official security and fenced-off management activities from the real work of the laboratory! Beck had the only telephone.

Another point of comparison, then and now, is the working environment. Nowadays as soon as graduates start to climb up the seniority ladder, they hope to get an office or at least a boxed-off cubicle to themselves, with desk, filing cabinet, telephone, a chair, personal computer etc, etc. Our Green Satin team worked in a wooden hut with benches and stools. You didn’t even have a dedicated area of bench although before long the hardware took a fairly static location so a work pattern was formed. The only office was a partitioned-off bit, open at the top where Geoff Beck worked. It was necessary because he had ministry and company visitors. We took the view that it maintained official security and fenced-off management activities from the real work of the laboratory! Beck had the only telephone.

We were issued with one screwdriver large, one screwdriver small, side cutters and round-nosed pliers: wire stripping tools were a later luxury. To prevent tools straying we each bound them with our own colour-coded wire. I still have some today – perhaps I should have handed them in when I retired. We were given a Marconi propelling pencil: lead for the pencil, and writing pads, were negotiable from Dudley Shearman! Most of the engineers were capable of operating machine tools – it depended on the Development Workshop foreman whether we were allowed to or not. It is a characteristic of design engineers to want their own workshop in their own laboratory, to use when and how they please. It is a characteristic of senior management to oppose such a notion!

Clerical services were very limited compared with today. No personal secretaries (except for very senior management); no word processors. We wrote all internal or external letters or reports in longhand and gave them to Dudley’s office, where Barbara Trevor, or Dudley himself, typed them, with carbon copies. If formal documents for a customer, or Internal Technical Memoranda were required in several copies. Stencils had to be typed. Any amendment or error-correction was a messy operation, with Tippex and overtyping (usually misaligned!). The office staff were heroes. By the way, DG Shearman was known as Dudley to us and as Gordon to others. I liked to think we were on first name terms.

Another difference, then to now, was in personal relationships. We addressed equals by their surnames. Our seniors addressed us by our surnames. We addressed them as Mister -, with many ‘Yes Sirs’ and ‘No Sirs’ in the course of conversation. If there was more than one person of the same name, a descriptor was added.

In the 50s most people smoked, and many affected, pipes. The habit had been encouraged in the HM Forces by the availability of cheap tobacco rations. We smoked over our work, but we did our best to clean out fag ends and ash from equipment to be delivered to our customers!

Rank was not clearly defined as it is today in career progression ladders. We were all Engineers, with some more senior than others; we all knew our relative status. Steps up the ladder were to Section Leader, or Group Leader as one became responsible for guiding the work of others. Nowadays titles have proliferated and become inflated sometimes to a meaningless jargon. In the 1950s Marconi’s top man, F N Sutherland was the General Manager.